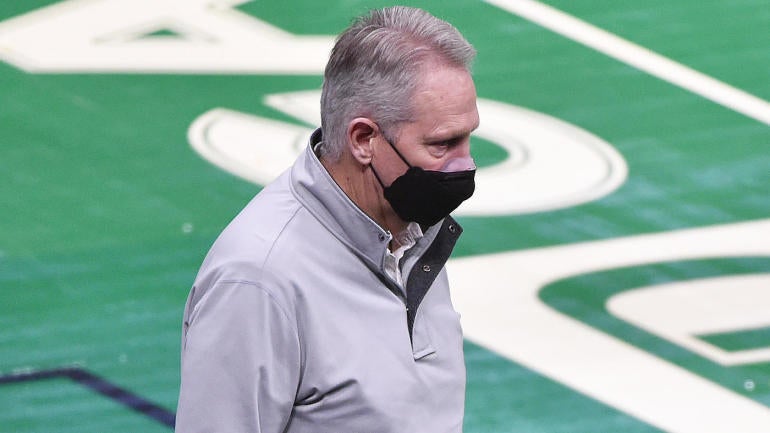

Danny Ainge's final defeat as president of basketball operations for the Boston Celtics fittingly came at the hands of the Brooklyn Nets, though perhaps not for the reasons you'd think. While Kyrie Irving getting the better of his former team certainly stings, it was James Harden who truly signaled the NBA's seachange. For years, Ainge built a reputation as the league's premier asset hoarder, yet when a disgruntled superstar hit the market, he couldn't outbid the team he'd infamously robbed blind seven years earlier.

"We had numerous conversations, but the price wasn't changing and the price was really high for us," Ainge said on 98.5 The Sports Hub's "Toucher and Rich Show" after Brooklyn acquired Harden. "It was something we didn't want to do," he said. "Even the people in our organization that respected [Harden] and wanted him more, I think unanimously we decided it wasn't the time for us and it wasn't the price."

CBS Sports HQ Newsletter

Your Ultimate Guide to Every Day in Sports

We bring sports news that matters to your inbox, to help you stay informed and get a winning edge.

Thanks for signing up!

Keep an eye on your inbox.

Sorry!

There was an error processing your subscription.

That would have been an almost unthinkable position for Boston to take earlier in Ainge's tenure. He spent multiple seasons in the lottery last decade specifically to accumulate the assets necessary to one day deal for a disgruntled star. He had so little competition on that front that he was able to nab two in a single offseason -- Ray Allen and Kevin Garnett, a feat that hasn't been matched on the trade market since. His foresight on that front spawned many copycats, several of whom came either directly or indirectly from his own tree. Daryl Morey got his start in Boston, and after leaving for Houston, he helped develop future GMs Gersson Rosas, Monte McNair, and, most famously, Sam Hinkie. The competition for superstars got stiffer. Ainge zagged.

He had good reason to. There's no reason to be hasty with Jayson Tatum and Jaylen Brown in their mid-20s. Boston might've gone all-in for the right superstar, and all indications suggest it viewed Anthony Davis as such. But Ainge's patience exacted a different sort of toll, turning Boston into a sort of guinea pig for the side effects of late-stage asset accumulation. The Celtics could have traded for Jimmy Butler. Or Paul George. Or Kawhi Leonard. Or any number of other players. But with each passing miss, their mountain of assets grew steadily less appealing.

Premium draft picks became underwhelming draft picks. Boston had so many first-rounders that none got the developmental opportunities needed. Terry Rozier voiced frustration over his limited minutes and is thriving in a steadier role with Charlotte now. Others like James Young, Guerschon Yabusele and R.J. Hunter scarcely saw the floor at all. That mountain shrunk into a hill. Then a dune. Then, as of this offseason, nothing at all. Once they selected Aaron Nesmith with the No. 14 overall pick in last November's NBA Draft and dealt No. 30 overall pick Desmond Bane, their surplus had officially been spent. For the first time in almost a decade, the Celtics officially did not own a single first-round pick originally belonging to another team. Aside from their dalliance with Irving, they had no third superstar to show for it.

It poses a fascinating contrast to the Brooklyn team that handed Ainge Tatum and Brown on a silver platter. The Nets started with nothing from an asset standpoint, which made the few assets they did have all the more valuable. Caris LeVert and Jarrett Allen got all of the minutes Boston's rookies had to fight for, and they grew into meaningful components of the Harden trade in the process. Joe Harris benefitted from similar opportunities and is now a core starter for the Nets. They made every asset count because they had to. Boston's assets depreciated one another through sheer volume.

Ainge took drastic steps to retain alternative forms of flexibility from there. Rather than sign-and-trade Gordon Hayward for players, he sent Charlotte a second-round pick to help create the biggest trade exception in NBA history at $28.5 million. That exception was later filled by Evan Fournier, hardly the star Boston likely hoped for. The last one he nabbed, Kemba Walker, was made possible only through the departures of Irving, Rozier and Al Horford. Timing matters as much as competence. Brooklyn happened to return to the postseason just as Kevin Durant and Kyrie Irving became available. Boston's appeal crescendoed just as the father of their prized target was going on television compelling the Celtics not to trade for his son.

Opportunities to trade for stars are rare. Boston passed on several. Brooklyn seized the moment when it came and has a championship favorite as a result. It isn't clear just how close Boston came to claiming Harden. Most reports suggest that Jaylen Brown was off the table, but Boston, like Brooklyn, owned all of its first-round picks and could have surrendered them in a similar package. Maybe Houston preferred Brooklyn's picks (completely justifiably, considering the ages of Tatum and Brown). Maybe Boston lacked Brooklyn's imagination in offering every single pick it had. Even without Brown or Tatum, the Celtics should have been able to make a competitive offer.

They didn't ultimately seal the deal, a disappointment that has become all too familiar in recent years. Boston may have pioneered the strategy Brooklyn secured Harden with, but the Nets took it to a level he Celtics couldn't stomach. The Clippers had already done the same with George. More teams will follow. The NBA changed around the Celtics. What they considered aggressive over a decade ago has now become standard NBA fare.

Harden's Nets aren't going anywhere. The Celtics, as presently constructed, are not going to beat them. Though not to the same extent, they are now the underdogs that the Nets once were. Brooklyn took bold steps to change that. It's Brad Stevens' turn to do the same, and unlike Ainge, he won't have a treasure chest of picks giving him a head start. That might not be the worst thing. Stevens has now seen Ainge's entire roadmap. He's endured the pitfalls of his patience. Boston's unbridled ambition granted the Celtics Garnett and Allen. The rest of the league has discovered that inefficiency. Now, it's up to Stevens to find the next one.