Dec. 23, 1975 is a historic date in baseball, one that forever changed the game. On this date 40 years ago, free agency was born.

Some background: Up until that date, owners were free to keep their players as long as they wanted thanks to the reserve clause. As an added bonus, they were able to pay them pretty much whatever they wanted. Trades and releases were the only way players changed teams.

In a nutshell, the reserve clause allowed owners to sign their players to one-year contracts year after year. The reserve rights even applied following retirement -- if a player retired then wanted to attempt a comeback, he was still property of his former team. Owners could renew a player's contract at any salary if the two sides couldn't negotiate a deal.

Following the 1975 season, Dodgers right-hander Andy Messersmith was unable to agree to a contract with the team. He went 20-6 and finished second in the Cy Young voting in 1974, then went 19-14 and finished fifth in the Cy Young voting in 1975. The Dodgers renewed his contract at the salary of their choosing for the 1976 season. The players' union filed a grievance on Messersmith's behalf.

Meanwhile, longtime Orioles lefty Dave McNally was at the end of his career, so much so that he retired in the middle of the 1975 season. The union, looking to bolster Messersmith's case, added McNally as a second plaintiff to the grievance because the Expos (his team at the time) still controlled his rights after retirement.

The grievance was heard by arbitrator Peter Seitz, who interpreted the reserve clause to mean the team was entitle to one single contract renewal, not perpetual renewals. Messersmith and McNally were ruled able to sign with any team. Free agency was born. MLB appealed the ruling, of course, but nothing came of it. Commissioner Bowie Kuhn fired Seitz shortly thereafter.

Under Seitz's original ruling, all players would become free agents after one contract renewal, which essentially meant all non-rookies would become free agents each offseason. The union was concerned having so many players in free agency would flood the market and drive salaries down, not up.

So, to avoid such a problem, MLB and the union agreed to a new deal allowing teams to hold on to their players for six years before they could become free agents. The particulars have changed over the years -- the arbitration system was added, for example -- but the same rule applies today. Players need six years of service time to qualify for free agency.

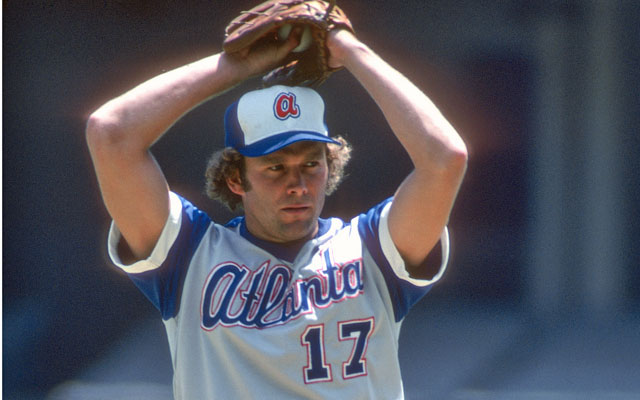

Messersmith signed a three-year, $1 million contract with the Braves following the ruling -- that was major money back then -- and had a very good 1976 season (11-11, 3.04 ERA) before things started to fall apart. McNally stayed retired but was integral to the grievance because he was a retired players whose rights were still held by a team.

Seitz's ruling changed the game forever. Free agency meant salaries exploded, but it also helped generate more interest in the game than ever before.