Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred made good on the league's long-standing threat to cancel regular season games on Tuesday evening, scrapping the first two series of the year. Manfred's announcement came after negotiations on a new Collective Bargaining Agreement fell apart during the afternoon, causing the two sides to pass a league-imposed deadline without a deal.

This season will mark the first time the regular season has been compromised by a work stoppage since 1995, as well as the first time in league history that an owner-imposed lockout has resulted in missed games.

The average fan, or anyone who had tuned out for the past three months, might find themselves wondering: how did the lockout reach this point? For a refresher and/or an explainer, allow us to highlight three reasons why a deal wasn't reached.

1. An unnecessary preemptive shot

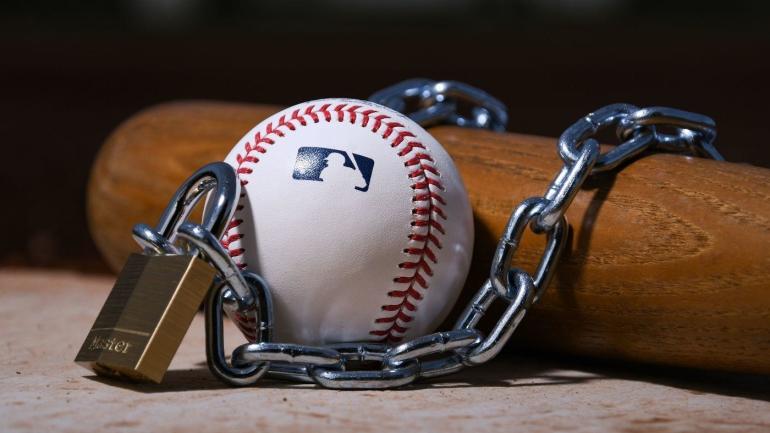

Let's start from the top. The league didn't have to impose a lockout when it did, with the expiration of the last CBA on December 2. The two sides could have continued to operate under the sunset terms of the last CBA while negotiating on the side. The league nevertheless opted for the padlock, citing it as a defense mechanism that they hoped would hasten negotiations and prevent the loss of regular season contests.

Obviously that didn't work.

To be clear, instituting the lockout wasn't about fast-tracking negotiations (as we'll cover in more depth in the next subheading); it was about winning the leverage game. If the league had operated as normal, without locking out the players, then it risked the players having the ability to strike in spring training, or at some point during the regular season or playoffs, thereby gaining leverage for their side. The owners wanted to prevent that scenario from becoming a reality; hence a lockout that, at minimum, didn't aid negotiations and, instead, likely caused additional strafe between the sides.

2. Playing waiting games

As noted above, the league claimed that the lockout would hasten negotiations. The owners then waited more than six weeks to make their first proposal to the players, eating into valuable time that could have been used to preserve a 162-game regular season and undercutting one of the stated reasons for the lockout in the first place.

Waiting has become a signature strategy under Manfred's watch, and it seems likely that the league and the owners view it as a way to test the union's resolve. The league and players couldn't come to an agreement in 2020, allowing Manfred to unilaterally impose a 60-game season that June. Last spring, the league waited until March to announce which rules would carry over and which would not.

The same is true of the league's self-imposed deadlines; they were designed in part to force the union to make a snap decision that might work against their best interests. The two sides didn't start meeting and swapping proposals on a consistent basis until the final 10 days, when they relocated to a spring training facility in Florida. The impetus for those talks? A league-set deadline of February 28. The league moved that deadline to 5 p.m. on Tuesday only after negotiations carried deep into the night, providing that the deadline was arbitrary in the first place.

3. League's unwillingness to move on big issues

Most coverage of negotiations play up the idea of conceding and meeting in the middle. An honest analysis of the talks between the owners and the players would find that the latter camp consistently ceded ground while the former did not.

Indeed, the league classified proposals that altered revenue sharing or the Super Two qualification threshold as non-starters. Moreover, it played hardball with other hot-button issues, like the league minimum compensation and the Competitive Balance Tax, offering deals that were wholly unreasonable.

The league's CBT proposals, for instance, would have placed the threshold to $220 million in each of the next three seasons; a laughable increase when compared to the revenue gains the league would have experienced with an expanded postseason, seemingly the league's top priority throughout the negotiations.

The players, for their part, requested a CBT threshold beginning at $245 million next season and were willing to give the league a 12-team postseason that would have created an additional $85 million in revenue each October.

Put another way, as Baseball Reference's Sean Forman did on Twitter, the players were asking for $1 to $2 million more per team per year in minimum salaries; $3 million more per team per year in pre-arbitration bonus pool money; and a CBT threshold that reflected the league's growth in revenues. The owners deemed that too much to give, or come close to giving.

It's to be seen when the next round of negotiations take place and what they hold. For now, the only certainty is that the regular season will not begin on time.