The ongoing Oakland A's relocation tragi-comedy has served as an acute reminder about how entitled sports team owners feel when it comes to getting public funds for stadium projects. This of course is not a new phenomenon, and the line of owners looking for such handouts is a constant presence across major professional team sports.

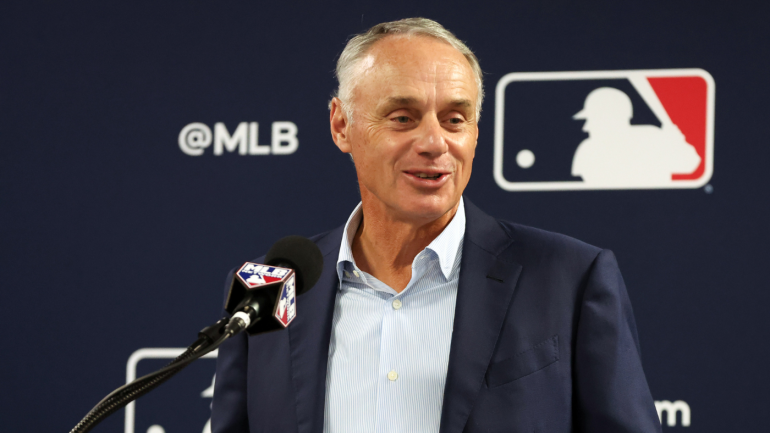

On Monday, Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred was asked about this issue during his appearance at the 2024 Associated Press Sports Editors Commissioners Meetings. Here's his response:

"There has been a long history of public financing of not just baseball but sports venues in general. Expenditure, public funds that people have seen as justified as part of the quality of life and entertainment opportunities available to residents in particular cities, as well as an economic driver. Certainly on the latter point, I recognize this is something that some will debate, but whatever the merits of it across the board, investment in baseball facilities is the best of the (sports) investments because of the number games. It just drives more people into the market for entertainment than any other sport just based on sheer volume. I do think that in today's world, almost all projects, whether they be new stadiums, major renovations, all of those types of projects, almost without exception -- and this is different than it was a couple of decades ago -- are public-private partnerships with owners of teams making really substantial, hundreds of millions of dollars, investments. I think the Las Vegas project is a great example of that: it's a billion-and-a-half dollar project where the public financing, I think the number is $380 (million) and the rest of that investment is going to be made by the owner."

This is not a notable departure from the usual spin put on such things from team owners or those who represent their interests. One person's "public-private partnership" is another person's corporate welfare. Manfred's remarks, however, do invite fresh appraisals of these arguments typically put forth to justify putting tax dollars toward stadium construction.

Manfred is correct that the practice of public financing of pro sports venues is an entrenched one. Just as entrenched, however, is the evidence that the "economic driver" aspect of ballpark construction is nonexistent. Academic research on the issue is unequivocal: Cities and states do not receive anything close to adequate return on their investments in pro sports facilities, be they ballparks, basketball arenas, football stadiums, or whatever. To cite just one, here's the upshot of economist Robert Baade's sprawling 1994 study on 48 cities across 30 years:

"Far from generating new revenues out of which other projects can be funded, sports 'investments' appear to be an economically unsound use of a community's scarce financial resources."

More specifically, Baade found that of the 30 cities with new venues, 27 showed no signs of measurable economic growth, and the other three saw per-capita income decrease after the respective venue was funded and constructed. This is not an outlier study. It's representative of an overwhelmingly sturdy consensus, and no glib dismissals from those hoping to defend handouts can change those facts.

The other noteworthy part of Manfred's comments is the $380 million price tag for the public should the A's move to Las Vegas actually happen. Manfred's recollections are correct, in that $380 million is the purported figure that Nevada taxpayers will cover. Indeed, Nevada Gov. Joe Lombardo signed a $380 million public funding bill back in mid-June. However, as Neil DeMause explained at Field of Schemes, the actual price tag on the public contribution will almost certainly be much, much higher. This is no accident, as owners and the commissioners who advocate for them have a chronic habit of soft-pedaling how much money the public is going to wind up contributing to projects that often turn into boondoggles. Even in the rare project touted as being wholly financed by private money, you often see valuable city-owned land being donated, infrastructure improvements that otherwise would not have been necessary being ponied up for by the public, and property-tax abatements granted to the team that hurt the municipal bottom line as much as any direct debit would.

Ignoring these realities is of course what's necessary to make the project seem more palatable to a suspicious public. Speaking of which, it's no accident that when these projects are put to a public referendum, they usually fail. That was the case recently in Kansas City, as both the Chiefs and Royals sought handouts; more than 58% of voters rejected the state tax referendum in April. This is why teams and local officials pining for some kind of vanity project often do what they can to avoid letting the public have a direct say in how their money is spent. The A's and team-friendly civic leaders in Las Vegas have done just that. Grassroots opponents of using tax dollars for sports facilities usually want nothing more than to put it to a vote, and those on the other side are hellbent not to let that happen because they know how it goes when the hoi polloi get asked whether a billionaire team owner should get some of their tax dollars.

Very likely, the response to questions such as the one posed to Manfred won't change – it will remain a mix of obfuscation and evasion. You, though, have the power to acknowledge the facts and not believe what you're being told, no matter how many times you hear it.