CHICAGO -- Most people take the Red Line to Wrigley Field. If you want to walk a little and maybe dodge a bit of the pregame crowd, though, you can take the Brown Line to Belmont, head west a few steps, and then stroll a little more than half a mile north up Sheffield deep into Wrigleyville. When you get to Roscoe Street, you can make the first base-side light bank climbing above the rooftops. The Dodgers and Cubs will play Game 4 of the 2017 NLCS there Wednesday night. The day before, the Yankees had pulled even with the Astros in the ALCS. The tantalizing possibility that the Yankees and Cubs could meet in the World Series for the first time since 1938 is a remote one at this point, thanks to the Dodgers' dominance of the latter. But it's still possible as Game 4 looms.

You've got some time before first pitch, so you pass the Addison "L" stop, Murphy's Bleachers, and the bleacher edifice, which looks something like the stern of a ship with "Chicago Cubs" in red, gassy letters. You cross Waveland and then Grace as you make your way to the 3800 block of Sheffield -- two blocks north of the ballpark. Here it is, the old six-story building at 3834 North Sheffield that dates back to the 19th century, the one with the chessboard stone work under some of the windows ...

There's a story here. This building used to be the Sheffield House Hotel, and before that it was the Hotel Carlos, as the baroque carvings on the entryway still announce. All of that, though, was before a reported 53 code violations ended the building's days as a single-room occupancy hotel. It's now luxury condos.

Back in the 1930s, the Hotel Carlos was a popular choice for Cubs players seeking a place to live during the season. Shortstop Billy Jurges, who toiled for the Cubs from 1931 through 1938 before being traded to the Giants, was one of those players. He lived in room 509. Jurges' girlfriend, Violet Popovich, also lived in the Hotel Carlos. On July 6, 1932, not long after Jurges broke things off, she wrote the following note:

"To me life without Billy isn't worth living, but why should I leave this earth alone? I'm going to take Billy with me."

At some point after writing those words, Popovich on July 6, 1932, made her way to room 509 and with a .25 caliber handgun shot Jurges once in the ribs and once in the left hand. Then, apparently after turning the gun on herself, shot herself in the arm during a struggle for the weapon. Jurges found a teammate in the hallways, who summoned the Cubs' team doctor. Jurges and Popovich were rushed to Illinois Masonic Hospital, where they survived their wounds. Jurges declined to press charges, and is said to have refused to appear at her trial as a witness. To hear Jurges tell it years later, Popovich had really wanted to kill Kiki Cuyler, whom she'd also supposedly dated. According to Jurges, she'd put a note on the mirror of Cuyler's room at the Hotel Carlos that blared -- simply and declaratively -- "I'm going to kill you." For his part, Cuyler denied ever having anything to do with her. Whatever the truth, it was Jurges who paid the fare on that day.

Popovich was arrested and charged with assault with intent to kill and appeared before Judge John A. Sbarbaro, a Cubs fan of some renown at the time, it is said. In large part because of Jurges' unwillingness to press charges, Sbarbaro ruled that "the case is dismissed for want of prosecution."

Because this is Chicago and because this is 1932, the story ends no other way ...

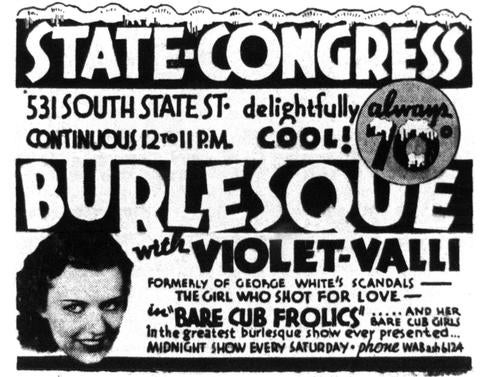

Violet Popovich had been a dancer before all this happened, and once she was loosed from any legal consequences she capitalized on her salacious infamy. Violet Popovich was "Violet Valli" onstage, and after the jilted lover shot the Cubs' shortstop, her career found a new arc. Billed on occasion as "Violet (I Did it for Love) Valli -- the Most Talked About Girl in Chicago," Popovich signed a 22-week contract to sing and dance in nightclubs and theaters all around the city.

As mentioned above, the Cubs and Yankees -- still a possible World Series engagement in the here and now -- last clashed for the belt and the title back in 1938. But the Cubs and Jurges (a Bronx native, coincidentally) and the Yankees also met in the Fall Classic back in '32. As you walk past what was the Hotel Carlos on Sheffield on your way to the Dodgers-Cubs tilt on this fall night, you have cause to remember the story of 1932 -- the baseball season and the year at large in America.

The Great Depression is in full flower, Prohibition is nearing an end, the Cubs and Yankees are bound headlong for each other, and their two cities -- Chicago and New York -- are on the brink …

In Chicago, mayor Anton Cermak is tasked with cleaning up the city in advance of the 1933 World's Fair, and that means taking on the mob. The mob, meanwhile, is in transition because Al Capone is headed to federal prison and bootlegging revenues will soon dry up. As well, Cermak and Chicago will host the Republican and Democratic National Conventions. It's the latter that will conclude in dramatic fashion and -- with the nomination of Franklin D. Roosevelt -- wind up changing the course of American history. That's to say nothing of the fact that no city was hit harder by the Depression than Cermak's Chicago.

In New York, the Yankees didn't just win the pennant -- they stormed to it. It was Ruth's last great season, Lou Gehrig continued to establish himself as a legendary talent, and the rotation was baseball's best. The Yankees took the pennant by a full 13 games. They also led the league in attendance and, like the Cubs, managed to turn a profit despite a collapsing economy.

In the end, this is the story of a transformative year in the two most important American cities. It's a story of political rebirth, crime, corruption, murder, and the indispensable presence of baseball -- as salve, distraction, or complement -- in the American narrative ...

Major characters

Anton Cermak: The overdetermined mayor of Chicago and a former coal miner with a third-grade education.

A Czech-born immigrant, Cermak broke the Irish-Catholic -- and Republican -- stranglehold on Chicago politics. To do so, Cermak built a broad coalition and enfranchised the long-ignored Eastern European populations of Chicago. Cermak's political organization evolved into the Cook County machine and led to utter domination of city politics by the Democratic Party -- a domination that is still with us.

In 1932, though, Cermak faced a number of daunting challenges. The Great Depression reached unimagined depths, and Chicago, as the manufacturing center of the U.S., was particularly devastated. Cermak had to deal with a "tax strike," an inability to pay city employees for several months, close to 50 percent unemployment by October, unrest within labor unions, eviction riots, an exhausted city emergency-relief fund, a string of bank failures in the Loop, and -- as a symbol of the times -- "Hooverville" tent communities all over the city.

Despite the hard times, Cermak was also readying the city to host the Democratic and Republican National Conventions in 1932. In particular, the Democratic Convention would challenge Cermak's political instincts. Once the convention descended upon Chicago Stadium in June, Cermak set to work. As leader of an urban political machine and as someone feverishly opposed to Prohibition, Cermak was duty-bound to support Al Smith of New York, the Tammany-backed "Wet" who had been the party's nominee in 1928. But New York governor Franklin Roosevelt entered the convention as the favorite.

Cermak did his best to undermine Roosevelt. He packed the galleries with Smith supporters, worked back channels and used his influence to help the "Stop Roosevelt" movement however he could. Yet as the balloting progressed and Roosevelt's grip on the nomination seemingly weakened, Cermak alone sensed in FDR's campaign a hidden strength. Cermak's city badly needed federal dollars in the years to come, and he could scarcely risk alienating the new president (almost certain to be the Democratic nominee, given the widespread disaffection with Hoover). So Cermak switched his support to Roosevelt and led a Smith-to-Roosevelt exodus of delegates. Roosevelt, with time running out and by a narrow margin, clinched the nomination, thanks in large part to Cermak's late-hour maneuverings.

Still and yet, Cermak had to prepare for the 1933 World's Fair, which Chicago would host in celebration of the city's centennial. That meant cleaning up the streets and taking on the mob.

Thanks to the power and ubiquity of Al Capone's gangsters and the corrupt misrule of Cermak's predecessor, "Big Bill" Thompson, Chicago was seen as a badland awash in graft and violence. The St. Valentine's Day Massacre of 1929 only reinforced such perceptions. But the World's Fair presented a chance at redemption. So Cermak, in his inaugural address, pledged to "present to the world a City, well governed and well ordered, and with a record for the suppression and prompt punishment of lawlessness equal to that of any other large city in the United States."

Cermak, though, was no high-minded paladin -- to take on Capone's men he enlisted the help of North Side gangster Roger Touhy. The distinction? Cermak would countenance gangsters of Touhy's ilk because they were discreet. They weren't, unlike Capone, perpetrating their crimes in full view and, and they weren't, unlike Capone, showy and open with their ill-gotten wealth.

Al Capone: The boss of the Chicago mob who was headed to federal prison but whose dominating absence would still be keenly felt.

Capone, to the shock of many, was convicted in late 1931 on tax-evasion charges and sentenced to 11 years in the federal penitentiary. In May of 1932, he was transferred from the Cook County Jail to the federal prison in Atlanta. There, his contacts with the Chicago underworld were diminished. Eventually, Capone was shipped off to Alcatraz, which effectively ended any contact with the Chicago Outfit. Besides the loss of Capone, the mob in Chicago also faced the end of Prohibition, which threatened their most reliable source of revenue -- bootlegged liquor.

Frank Nitti: The inheritor of Capone's criminal empire.

It's Nitti whom Capone, just before his sentencing, tabs to lead the Outfit. It was a masterstroke. Nitti was in many ways a figurehead, while lieutenants like Tony Accardo, Paul Ricca and Murray Humphreys were more vital to the workaday success of the organization. Still, in July of '32 Nitti orders a (successful) hit on Red Barker (who's also vying for control), and at that moment it becomes clear who's now the mob boss of Chicago. On Nitti's watch, the Outfit will infiltrate trade unions, set up a far-reaching gambling enterprise, and even hold sway over a major Hollywood studio.

Murray Humphreys: The Outfit's point man in their efforts to take over the unions. Humphreys in so many ways embodied what made the Chicago mob the new face of organized crime. Humphreys was of direct Welsh descent and made it to the higher rungs of the Outfit despite not being Italian.

Lucky Luciano: The newly emerged head of the New York mob.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: The man who seizes the Democratic presidential nomination for president in Chicago, forges an uneasy alliance with Cermak, and breaks from Tammany Hall, the venerable, corrupt, and embattled political machine, back in New York.

Jimmy Walker: The dapper and foppish mayor of New York City. "Beau James" is a Jazz Age anachronism and a symbol of both Tammany corruption and aloof detachment from the miseries of the common people.

In New York, Walker faces his own challenges. He's on the verge of being forced out by the Seabury Commission on gravely serious corruption charges -- charges that will move him to flee to Europe. The investigation culminates in a showdown between Walker and then-Governor Franklin Roosevelt. Like Cermak, he's doing whatever he can to ensure that Al Smith wins the Democratic nomination for the presidency, particularly in the midst of an investigation that Roosevelt refuses to halt. Unlike Cermak, though, Walker will have no change of heart in the final moments.

Besides the political intrigute, Walker, also like Cermak, is faced with an evolving underworld in his city. In the wake of the Castellammarese War that ended in 1931, New York mobsters establish "The Five Families" and usher in the era of the American-born mafia leader. Walker, in contrast to Cermak, has no stomach -- and no cause -- for a fight with the seedier elements in his town.

Babe Ruth: The iconic ballplayer and one of the defining American figures of the 20th century. Back when Jimmy Walker was a state senator, he supposedly brought Ruth to tears in 1925 by scolding him for being such a noxious influence on the youth of New York. Ruth promised to do better. If he did, it was only in select outward-facing moments.

In 1932, Ruth, a man who redefined the possible, a man who happily submitted to his basest urges, remains not only relevant but also towering, even as the times make his excesses seem indecent rather than impish and playful.

Ruth began 1932 with a bitter contract holdout. Asked how he could justify asking for more money than President Hoover made, Ruth famously quipped, "I had a better year than he did."

Holdout over and season begun, Ruth, age 37, began crafting his last great campaign. His 41 homers help the Yankees to the pennant, but his World Series performance further burnished his legend.

On the field, it all led up to Game 3 of the World Series at Wrigley Field. Roosevelt threw out the first pitch, and he and Cermak watched the game together in box seats near the Cubs' dugout. In the fifth inning, Ruth gestured toward center field and then hit a towering home run to the exact spot toward which he appeared to be pointing. It would be Ruth's last World Series hit, and it would earn a permanent place in American lore as "The Called Shot." It probably wasn't a called shot -- Ruth was likely exchanging harsh words and threats with a Cubs team that had been mercilessly ribbing him all series -- but myth has a strong grasp.

Billy Jurges: The Cubs' 24-year-old shortstop who'll be shot.

Violet "Valli" Popovich: The jealous burlesque performer who'll shoot Jurges.

The Chicago Cubs: Chicago's team. Cermak's team.

But they were also the team of gangsters. Capone had once given a revolver, engraved with a personal message, to his favorite player, Kiki Cuyler, the Cubs' best hitter down the stretch in 1932. As well, the Cubs' star catcher Gabby Hartnett was once scolded by MLB commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis for posing for a photograph with Capone at a 1931 charity game against the crosstown White Sox. As a result, Landis banned players from fraternizing with fans. (Once Capone reported to federal prison, Landis lifted this order.) The Tribune and other Chicago dailies would blare Capone's predictions for his favorite team, and Capone and his successors would often supply the Cubs' president, William Veeck Sr., with cases of bootlegged champagne.

In 1932, though, the Cubs and the Yankees stand as the only profitable franchises in all of sports. In achieving as much, they symbolize the survival instincts and binding routines that will carry Americans through the "hard times" and the lacerating political rebirths to come.

The Cubs begin the season not long after the death of owner William Wrigley, and later in the year, yes, their starting shortstop would be shot by that jealous lover. Still and yet, the Cubs win the pennant and earned the chance to erase memories of their stunning collapse in the 1929 World Series. Getting there, however, wasn't easy. They were solid for the early months of the season, but by late July they had fallen to 5 1/2 games behind the Pirates. It's then that new president William Veeck Sr. fires his manager, the dour, misanthropic Rogers Hornsby, and replaces him with first baseman Charlie Grimm.

In contrast to Hornsby, "Jolly Cholly" is an affable, relentlessly positive sort. For a city so blighted, it's a welcome change. In some ways, the switch from Hornsby to Grimm symbolized -- augured, even -- what would happen months later when the country abandoned Hoover for the penetrating optimism of Roosevelt.

Indeed, the Cubs, for working-class Chicagoans, served as a foil to the misery about them. The day after the Cubs clinched the pennant, almost a half-million beleaguered Chicagoans turned out to watch a three-mile motorcade through the city. Cubs players filed past Mayor Cermak at the reviewing stand. "You have done a great job as baseball goes," Cermak told them. "You have done a greater job as civic duty goes."

The New York Yankees: New York's team. Jimmy Walker's team. The Yankees, much like modern New York, were forged in the backrooms of Tammany by their bygone owners, a gambler and a compromised former police chief.

Besides the municipal hostilities involved (driven largely by Chicago's chronic inferiority complex vis-a-vis New York), Yankee manager Joe McCarthy, who had been unceremoniously fired as manager of the Cubs following a pennant-winning campaign in 1929, was spoiling for revenge. As well, the Yankees were angry at the Cubs for not voting shortstop Mark Koenig, a beloved former Yankee who helped key the Cubs' stretch drive, a full share of World Series money.

The Yankees were Ruth and Gehrig and Bill Dickey and "Poosh 'Em Up" Tony Lazzeri and Red Ruffing and a colossus pretty well larded with future Hall of Famers. During a time when America seemed more vulnerable to collapse than it had been since the Civil War, the Bombers exuded measured and metronomic invulnerability. They belied the times about them.

Chronology of Events

Oct. 17, 1931: Al Capone found guilty on three felony counts of tax evasion and two misdemeanor counts of failing to file tax returns. A week later he will be sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Jan. 21, 1932: New York City mayor Jimmy Walker reaffirms his loyalty to Tammany Hall, even as Judge Samuel Seabury's inquiry into civic corruption begins to probe into the upper reaches of the Democratic organization.

Jan. 26, 1932:– William K. Wrigley, majority owner of the Chicago Cubs since 1919, dies. Control of the team falls to William Veeck Sr.

Feb. 1, 1932: After seeing his handpicked successor take over as Cook County president, Mayor Cermak also sees his handpicked successor assume leadership of the county central committee. Cermak, besides holding the mayoralty and all associated patronage, now controls 45 of 50 ward committeemen within the city and a majority even in the once Republican-controlled areas of the county. Cermak's accrual of power has, in the words of one historian, "never been equaled in local political history."

Feb. 2, 1932: Despite a strong urging to run for the state's top office, Mayor Cermak slates Henry Horner as the Democratic nominee for governor. Horner will become the first Democratic governor of Illinois in 20 years and first Jewish governor in U.S. history.

Feb. 5, 1932: Former New York governor Al Smith announces that, if chosen, he will accept the Democratic Party's nomination for President of the United States.

Feb. 9, 1932: Tammany officials first float the idea of Jimmy Walker as the nominee for Vice President.

Feb. 16, 1932: With the city of Chicago near bankruptcy, Mayor Cermak undertakes what the Chicago Herald and Examiner calls "the most searching retrenchment program ever attempted by a local government." The next day, Cermak will threaten to shut down all public institutions within the Chicago unless the Illinois legislature provides immediate aid to the city. In the coming months, Cermak will introduce wage cuts and freezes, eliminate vacations and sick leave, fire hundreds from the city payrolls and eventually reduce the city budget by an unthinkable $13 million. His ruthless but necessary measures will breed much resentment among rank-and-file city workers. "Every employee severed from the payrolls becomes a charge upon charity," Cermak tells his friends, "and a bitter enemy of the mayor."

Feb. 20, , 1932: Seabury's committee subpoenas financial records of Mayor Walker's executive secretary.

March 3, 1932: Mayor Cermak announces his support for Senator James Hamilton Lewis for President. Lewis of Illinois is one of many "favorite son" candidates with no real chance at the Democratic nomination. In truth, Cermak supports Al Smith because of Smith's steadfast opposition to Prohibition. However, Cermak wants to limit his associations with the Tammany-backed "Stop Roosevelt" movement.

March 16, 1932: After a lengthy and controversial holdout, New York Yankee outfielder Babe Ruth signs for $75,000.

March 18, 1932: Mayor Walker challenges Seabury to produce evidence against him.

April 24, 1932: Cubs star Kiki Cuyler breaks his ankle while trying to make a play in the outfield. He'll miss the next seven weeks.

May 4, 1932: Al Capone reports to the Atlanta U.S. Penitentiary and begins serving his 11-year sentence. The Chicago Crime Commission names Murray Humphreys as the new "public enemy number one."

May 9, 1932: The Chicago Herald and Examiner headline reads, "GANGLAND LEADERS OIL GUNS FOR WAR".

May 12, 1932: Chicago North Side gangster Ted Newberry announces his retirement. Later in the year, he will align with Cermak to move against The Outfit.

May 16, 1932: The Yankees tie a major-league record by recording their fourth straight shutout.

March 17, 1932: Frank Nitti, Capone's chief lieutenant, is discharged from Leavenworth prison in Kansas.

March 24, 1932: Nitti resurfaces in Chicago.

April 3, 1932: Meyer Lanksy and other New York mob leaders arrive in Chicago to discuss Capone's successor. Soon after, Nitti will assume command.

April 18, 1932: The New York Times reports that the a reconciliation between Roosevelt and Al Smith, his chief rival for the Democratic presidential nomination, has become "virtually impossible."

May 15, 1932: In perhaps his last great moment, Mayor Walker leads a "Beer for Taxation" parade through Manhattan.

May 19, 1932: The National League revokes the rule prohibiting players from fraternizing with fans.

May 24, 1932: Mayor Cermak publicly chastises Congress for being slow to provide federal aid to Chicago. He calls Congress "a font of Bolshevism."

May 25, 1932: Mayor Walker takes the stand in a public hearing to answer Seabury's charges of graft. "The whole nation is watching," comments the Times.

May 26, 1932: Governor Roosevelt meets with his advisers in Albany. They agree that he has the delegate total to win the Democratic nomination in Chicago. However, they also agree that the politically hazardous situation with Mayor Walker could alter that outlook.

June 1, 1932: Mayor Cermak makes the first of his many trips to Washington, D.C. to plead for federal assistance. "It's up to the federal government now," Cermak tells lawmakers. "We can't do it. The situation is desperate."

June 3, 1932: On the day John McGraw resigns after 30 years as manager of the Giants, the Yankees' Lou Gehrig becomes the first player in major-league history to hit four home runs in one game.

June 8, 1932: Judge Seabury sends a letter of his findings to Governor Roosevelt. In the letter, he calls Mayor Walker "unfit" to serve.

June 10, 1932: Mayor Walker seeks to delay Governor Roosevelt's decision on his fate until after the November elections.

June 13, 1932: In an attempt to pressure Governor Roosevelt, Tammany leaders meet with Al Smith to discuss pledging of the city's delegates at the Chicago convention.

June 16, 1932: Chicago mobster Red Barker, who aspires to get in on the Outfit's union racketeering, is gunned down on Nitti's orders. The move asserts Nitti's authority. On the same day, the Republican Party re-nominates Herbert Hoover at Chicago Stadium. Hoover wins the nomination of the first ballot, with 98 percent of delegates supporting him.

June 23, 1932: Governor Roosevelt orders Mayor Walker to respond, in person, to Seabury's charges.

June 24, 1932: Mayor Walker leaves for Chicago to fulfill his duties as a delegate at the Democratic National Convention.

June 27, 1932: Judge Seabury arrives in Chicago for the convention. Both he and Al Smith speak out against Roosevelt's attempt to change the convention's mandate that the nominee must receive pledges from at least two-thirds of delegates. The old rule will be upheld.

Late June, 1932: Thanks almost entirely to Mayor Cermak's backroom machinations, the Democrats incorporate in the party platform a call for repeal of the 18th Amendment and an end to Prohibition.

Late June, 1932: Working behind the scenes, Mayor Walker prevents the Tammany vote from defecting to Roosevelt.

Late June, 1932: On the eve of the fourth ballot, Mayor Cermak learns that Smith cannot win. He resists, however, the urge to defect to Roosevelt, mostly to pacify the Irish elements with the Cook County Democratic Party.

Late June, 1932: On the fourth ballot, Roosevelt's handlers persuade the California and Texas delegations to defect. Thus Roosevelt secures the nomination. Only after do Illinois and Indiana, led by Cermak, soon follow but only after resisting Roosevelt's earlier entreaties.

June 30, 1932: The Cubs take the field as the last team in the majors to wear uniform numbers. They go on to shut out the Reds, but four days later they will cede first place to the Pirates.

July 6, 1932: Jurges, following a win over the Phillies, is shot by Popovich at the Hotel Carlos, two blocks from Wrigley Field.

July 15, 1932: Mayor Cermak takes to the radio airwaves to appeal to wealthy Chicagoans to pay the back taxes they owe.

July 21, 1932: Outfit hitmen gun down Patrick Berrell, a high-ranking Teamster official who had resisted the takeover. Thereafter, many other union leaders bow to the Outfit's wishes.

July 22, 1932: Just 16 days after being shot, Billy Jurges returns to the Cubs' lineup.

July 26, 1932: Mayor Cermak announces a two-week wage freeze for Chicago city employees. Municipal court judges refuse to accept the freezes.

Aug. 2, 1932: The Cubs lose in Brooklyn and drop to five games behind the Pirates. On the train to Philadelphia, Veeck and player-manager Rogers Hornsby engage in a heated argument. The argument carries over to Veeck's Philadelphia hotel room, and he eventually fires Hornsby as manager, in part because of the team's recent struggles and in part because of Hornsby's gambling debts. Veeck names first baseman Charlie Grimm as the new manager. The Cubs will respond by winning 20 of their next 25 games.

Aug. 5, 1932: The Cubs purchase the contract of shortstop Mark Koenig, a former Yankee, from the minor leagues. Koenig will go on to bat .353 for the Cubs.

Aug. 11, 1932: The Cubs beat the Pirates and reclaim first place for good.

Aug. 12, 1932: The removal hearing of Mayor Walker begins in Governor Roosevelt's chambers in Albany. It marks the first time a governor has sat in judgment of a New York City mayor.

Aug. 13, 1932: Commissioner Landis clears Hornsby on charges of borrowing money from Cubs players to pay off gambling debts.

Aug. 17, 1932: Mayor Walker files court documents seeking to have hearings before Governor Roosevelt declared illegal. Two days later, his plea will be denied.

Aug. 21, 1932: One Tammany official threatens a "resort to arms" if Mayor Walker is forcibly removed from office.

Aug. 31, 1932: Grimm, after making a complicated series of substitutions, winds up batting Zack Taylor after he'd already been removed from the game. The opposing New York Giants fail to protest, and the Cubs go on to win 10-9 on a Cuyler home run. In a nod to rivalry between both cities, the New York Times and the Chicago Daily Tribune print differing box scores of the game.

Sept. 1, 1932: William Randolph Hearst urges Mayor Walker to resign.

Sept. 2, 1932: Even as Governor Roosevelt weighs testimony and evidence, Mayor Walker announces, through a letter to the public, his resignation. In the same letter, he assails Roosevelt's credibility and standing. Roosevelt accepts Walker's resignation without comment. Tammany threatens to slate Walker for reelection in the fall.

Sept. 3, 1932: Mayor Cermak travels to Europe to promote the World's Fair. "They all use the dole over there," he says upon his return to Chicago. "Americans want work."

Sept. 8, 1932: Ruth is sidelined with severe abdominal pains, an affliction he believes to be appendicitis.

Sept. 12, 1932: The Yankees clinch the American League pennant with their 100th victory of the season. It's their record 200th straight game without being shut out.

Sept. 20, 1932: The Cubs clinch the National League pennant.

Sept. 22, 1932: The Cubs announce that they will grant no World Series shares to former manager Rogers Hornsby and, most controversially, just a half-share to shortstop Koenig.

Sept. 28, 1932: Keyed by a Gehrig home run, the Yankees beat the Cubs 12-6 in Game 1 of the World Series.

Sept. 29, 1932: Lefty Gomez shuts down the Cubs in a 5-2 Yankee win in Game 2.

Oct. 1, 1932: Back in Chicago, Democratic Presidential nominee Roosevelt, flanked by Mayor Cermak, throws out the first pitch of Game 3. In the fifth inning, Ruth appears to gesture toward center field and then, moments later, hits a home run to that precise spot. One New York paper will declare it the "Called Shot," which will survive in American lore to this day and beyond. The Yankees go on to win the game, 7-5

Oct. 2, 1932:– The Yankees complete the sweep by winning Game 4, 13-6. It's their record 12th straight World Series game victory.

Oct. 14, 1932: Commissioner Landis denies Hornsby's appeal for a share of the Cubs' World Series money.

Nov. 1, 1932: Cermak orders three separate raids on Outfit strongholds. In all 17 mobsters are arrested. Nitti, though, is not one of them.

Nov. 8, 1932: Roosevelt defeats Hoover by a landslide margin and becomes the 32nd President of the United States.

Nov. 10, 1932: Jimmy Walker and his mistress, the actress Betty Compton, leave for Europe. There, Walker will obtain a divorce from his wife and marry Compton in France. He won't return to the States for another five years, when taxes charges against him are finally dropped.

Dec. 19, 1932: Cermak dispatches three police detectives to the LaSalle-Wacker building in the Loop. Around noon, they kick in the door of Suite 554 and find Nitti and two associates inside. The two associates are hustled out into the hallway leaving Nitti alone with Sergeants Lang and Callahan. Callahan holds Nitti's wrists behind his back, and Lang fires a shot into Nitti's neck and two more into his torso. Lang then fires a final shot through his own hand. He tells other detectives arriving to the scene that Nitti first first. Lang produces a handgun he claims was Nitti's. Nitti, near death, is taken to the Bridewell House of Corrections instead of the nearest hospital.

Dec. 21, 1932: Nitti is allowed to post bail and his father-in-law, a prominent Chicago surgeon, has him transferred to Jefferson Park Hospital. There, doctors upgrade his chances of survival to 50-50.

Dec. 23, 1932: Cermak increases his personal security detail and moves his headquarters from the Congress Hotel to a private bungalow atop the Morrison Hotel. He begins wearing a bullet-proof vest.

Jan. 7, 1933:– The body of Cermak cohort Ted Newberry is found in rural Indiana.

Feb. 14, 1933: Cermak leaves for Miami, in part, some speculate, to escape the blowback from the Nitti hit and in part to curry favor with Roosevelt, whom he worries he spurned for too long at the convention. Cermak knows that Roosevelt can provide the federal aid that Chicago so badly needs, and he believes he can persuade him to hand it over, as well as giving him control of federal patronage positions in Chicago and Illinois. "Roosevelt is not only weak in the legs," Cermak tells an associate after arriving in Miami, "he's also weak in the head."

Feb. 15, 1933: As Roosevelt greets the crowd at Bayfront Park in Miami, Cermak approaches the reviewing stand. Shots ring out, and Cermak is one of four struck by the bullets. Giuseppe Zangara, an Italian anarchist is arrested. He claims Roosevelt was his target, but the conspiratorially-minded insist the Outfit dispatched him to kill Cermak. Cermak is whisked away in Roosevelt's limo, as the president-elect cradles him in his arms. "I'm glad it was me instead of you," Cermak supposedly tells Roosevelt.

Feb. 19, 1933: Cermak's secretary comes to visit him in his Miami hospital and address pressing city business. "So you arrived all right," Cermak says to her. "I thought maybe they'd shot up the office in Chicago, too."

March 2, 1933: Beset by illness and infection, Cermak takes a turn for the worse. Doctors move him into an oxygen room.

March 6, 1933: Cermak dies.

March 9, 1933: Cermak's body lies in state at City Hall. More than 76,000 line up to view the body. One city employee makes the rounds three times, and a nearby police officer asks him why. "I want to make sure he's dead," he answers.

Braid the narrative if you want. Intertwine the baseball and the politics and the crime in a way that seems cinematic or bookish. We do that, probably too much. Or just see it for what it is: A roiling year in which the two best teams in baseball seemed to reflect the tumult around them. Think of it as tide of loosely connected events that bruised against each other and changed things for having done so. Sometimes, the calendar houses more than it has a right to.

Think of it as a sprawling story of 1932 that comes to mind as you walk past 3834 North Sheffield Avenue on your way to watch the Dodgers and Cubs play in 2017.

As you turn back and walk south from what was the Hotel Carlos, you can make out through the leaves the lights of Wrigley illuminating the sky ahead of you ...

The sidewalk you walk on unspools as the same 1,500 feet or so that Billy Jurges walked on hundreds of times, from Room 509 to Wrigley and then back again. The lights ahead shine on the same field that Babe Ruth, in front of FDR and Anton Cermak, did or did not perpetrate a legendary moment in Game 3 back in '32. Arrange the pieces of the story a certain way and you think you see the faint lines connecting them. The lines might be real, or they might not be.

Sources for this story include the Chicago Tribune archives; New York Times archives, Jack Bales' WrigleyIvy.com; Happy Days Are Here Again : The 1932 Democratic Convention, the Emergence of FDR--and How America Was Changed Forever by Steven Neal; Electing FDR: The New Deal Campaign of 1932 by Donald A. Ritchie; Boss Cermak of Chicago: A study of political leadership by Alex Gottfried; After Capone: The Life And World Of Chicago Mob Boss Frank "the Enforcer" Nitti by Mars Eghigian Jr.; Once Upon a Time in New York: Jimmy Walker, Franklin Roosevelt, and the Last Great Battle of the Jazz Age by Herbert Mitgang; Beau James: The Life & Times of Jimmy Walker by Gene Fowler; Gangster City: The History of the New York Underworld 1900-1935 by Patrick Downey; The Encyclopedia of Chicago by the University of Chicago Press; and "The Show Girl and the Shortstop: The Strange Saga of Violet Popovich and Her Shooting of Cub Billy Jurges" by Jack Bales.