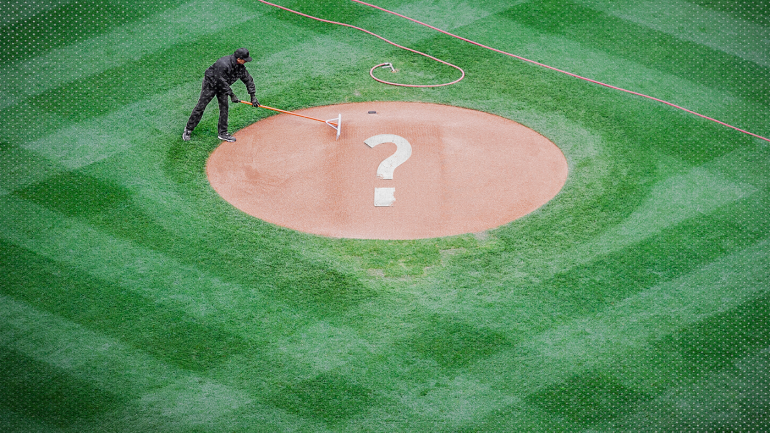

There was a moment earlier this season that, in one pitcher's mind, sums up what ails the Atlantic League of Professional Baseball, the country's most prominent independent baseball league. It was when ALPB president Rick White visited with a team to discuss forthcoming changes to the mound. On Aug. 3, at Major League Baseball's behest, the changes went into effect, with the ALPB moving its mounds a foot further back from their standard location of 60 feet, 6 inches from the rear point of home plate. "He said, 'Oh, you know, when the mounds go back, you pitchers, you're not going to really have to make any adjustments,'" the pitcher told CBS Sports, speaking on the condition of anonymity to avoid potential retaliation from the league.

"And then, the next words out of his mouth were, I swear to God, 'well, you might have to adjust where you release the ball.'" Or, in so many words, the most fundamental aspect of pitching.

White's amendment didn't plant the seeds of distrust in the players. Neither, it should be said, did the modified mound. But those words and acts, in combination with similar ones from years past, have fertilized what has grown into a garden of wariness that now divides the Atlantic League's players and leadership.

The pushed-back mound is only the latest experiment ALPB is conducting on MLB's behalf. The leagues reached a three-year agreement in 2019 that has since seen ALPB serve as a testing ground for various gameplay tweaks: the automated ball-strike system (a.k.a robot umpires); the three-batter minimum; stricter defensive positioning rules; wider bases; and the "double-hook" designated hitter (a team loses its DH whenever it removes its starting pitcher).

The partnership has proven mutually beneficial for the leagues. MLB has adopted several of the gameplay innovations it first commissioned ALPB to test at the minor- and major-league levels. Last year MLB rewarded ALPB, an eight-team league that had previously existed without a connection to affiliated ball since its inception in 1998, by christening it as an official partner league. If there is an exception, an invested group not being enriched by the arrangement, it's the players. They, the individuals responsible for the grunt work, have little say in the matter.

The players do, however, have big concerns about where the Atlantic League is heading. To them, the pushed-back mound is another example of MLB and the Atlantic League undermining their professional aspirations and toying with their livelihoods. The 61 1/2-foot mound is, above all, an isolated physical reminder of the interlocking issues that have come to define their careers: declining quality of competition and advancement opportunities; potentially increasing chances of injury; and a bevy of other labor-related considerations that players said pushed the league to the brink of a work stoppage ahead of the new mound's implementation. The players eventually stood down amid threats of career-altering consequences.

The leagues view the mound and the other Atlantic League experiments as a step in the right direction, toward baseball's future. But the players have been left wondering, who gets to define progress; whether or not it's always a good thing; and what happens to those who are left behind in its unforgiving wake?

'You lab rats deal with it'

After two weeks of the Atlantic League's great new experiment, the pitchers who spoke to CBS Sports agreed they had been able to make adjustments that rendered the extra distance from the mound to the plate irrelevant (albeit not the larger issues surrounding the topic).

"For me, it wasn't an issue," said one pitcher, who added that his softer-tossing teammates have more complaints. Another said: "Honestly, I think I'm actually pitching better." The reason? The additional movement their pitches enjoyed over the longer journey. "I was a little bit apprehensive at first," said Scott Shuman, a reliever with the Lancaster Barnstormers, "but after doing it for [multiple] outings now, it's the same old, same old."

White, the league president, did not have empirical data to offer during a phone call with CBS Sports, but he presented several of his own observations of how the Atlantic League's gameplay has changed since the new mound distance was installed. He believes more balls are being hit into play, with fewer plate appearances ending via strikeout; he believes pitchers are throwing more fastballs and fewer breaking balls; and he believes umpires when they tell him that pitchers' control, particularly over those breaking balls, has suffered since the change.

White's takeaway echoes the sentiments expressed by pitchers and MLB: "I think many people now who are close observers, or skilled participants in the games, are saying, 'this isn't having the effect, personally, that I thought it might.'" (An MLB spokesperson wrote in an email: "[We] are encouraged that pitchers in the Atlantic League seem to have made the necessary adjustments very quickly and avoided any significant disruption to the play on the field.")

If White's perception is correct about the Atlantic League's play taking a new form (analysis by Rob Arthur, a Baseball Prospectus author, indicates that it's not, and that strikeouts and home runs have actually increased since the change), then the move to the 61-foot, six-inch mound is having MLB's desired effect.

The past decade of play at the big-league level has been defined by the behavioral shifts by hitters and pitchers that precipitated the rise of the three true outcomes (strikeouts, walks, and home runs). As of Aug. 24, MLB is on pace for the lowest batting average since 1968; the second highest frequency of strikeouts; and the fourth-highest rate of home runs.

The interplay between variables complicates discerning what effect begets what effect, but the commonly accepted tale goes like this. Pitchers have become more skilled because of new technology that enables them better insight into their offerings; their fingers are more conductive to generating spin, thanks in part to the virality of grip-enhancing substances (something MLB is now trying to cut down on in the majors); and their gameplans now embracing liberal usage of their best pitches, even if they aren't fastballs. Batters, accepting the reality of the situation, have countered with launch-angle-generating swings tailored to maximize their damage.

The days of pitchers being lectured to "establish the fastball," or to "pitch to contact" early in counts are bygone. Now, teams are adamant about pitchers doing whatever it takes to coerce swings and misses. After all, there are three things that can happen when a batter swings at a pitch: they can hit it fair, they can hit it foul, or they can not hit it at all. Only one, the empty swing, is a definitively good outcome for the pitchers. And everyone knows it.

Once this philosophy yielded results, it became the dominant strategy. In turn, games have been reduced to perceived slogfests. MLB, understandably, feels the need to fine-tune the dials in order to achieve balance. Those behavioral shifts may have defined the last decade, but the next one will be made up of rulebook countermeasures, including, potentially, the 61 1/2-foot mound.

"It's a direct response to the escalating strikeout rate, where you're giving the hitter approximately one one-hundredth of a second of additional time to decide whether to swing at a pitch," Morgan Sword, MLB's executive vice president of baseball operations, told reporters of the mound move when the league announced the plans in April. "The purpose of the test and hope is giving hitters even that tiny additional piece of time will allow them to make more contact and reduce the strikeout rate."

If MLB likes what it sees from the Atlantic League and proposes a mound adjustment, it will be the first time the distance has been altered since 1893. The longevity of the 60 1/2-foot mound has obscured that it wasn't delivered through providence; it was the product of repeated trial and error. Besides, MLB has tinkered with the mound since. In 1969, it lowered the mound by five inches after the previous season, the so-called "Year of the Pitcher."

White, cognizant of the mound's history, points out that the league didn't test the shorter mound before implementing it in 1969. Someday, Atlantic League pitchers might be thanked by their big-league counterparts, or honored as pioneers. For now, they can't shake the feeling they're viewed as fungible guinea pigs. One pitcher, speaking from memory, recited the exact response MLB commissioner Rob Manfred gave when he was asked if an altered mound would lead to injuries: "That's why we're doing it in the Atlantic League."

Behind the scenes, the Atlantic League has attempted to assuage injury concerns related to the 61 1/2-foot mound by distributing a 2019 study conducted at the American Sports Medicine Institute.

ASMI's examination of the physical toll enacted by mound distances saw researchers gather 26 collegiate pitchers. They asked the pitchers to warm up before then throwing eight max-effort fastballs from three distances: the standard distance, then two and three feet farther from the plate. AMSI then analyzed all of the pitchers' motion data, as well as the pitch data for 21 of the participants. The researchers concluded in a four-page write-up that there was no significant "pitcher kinetic or kinematic differences" among the three distances. Further, they found that the "initial ball velocity, final ball velocity, and strike percentage" all remained static. The researchers did find effects on the "duration of ball flight, horizontal break, and vertical break," with each increasing in conjunction with greater distances.

The pitchers who spoke to CBS Sports scoffed at the study's application to their own situations. The pitchers wondered if or how the results would have changed if the pitchers were 32 years old instead of college-aged; or if they were throwing on no days' rest for the second or third consecutive game; or if they were rearing back for their 100th pitch of an outing, or to put an end to a high-leverage situation in a one-run game; or, dare say, if the pitchers were throwing sliders and splitters and curveballs to go along with their fastballs.

AMSI's researchers, to their credit, acknowledged the limitations of their work. "While changes in pitching biomechanics and ball velocity were not detected in this laboratory study, it is unknown whether pitchers would alter their mechanics over time when adapting to a longer pitching distance." The researchers unwittingly foreshadowed the Atlantic League's present state: "It would be valuable to supplement the laboratory data presented here with pilot field data from an adult baseball league(s) using increased pitching distance," the study said.

Even if the pitchers could take solace in knowing their mechanics wouldn't suffer from "kinematic differences" with the 61 1/2-foot mound, they disapproved of how the league introduced the change without a grace period. MLB and the Atlantic League announced in April that the change would come sometime during the 2021 season, but players did not get a week, or even a weekend, to test drive the new mound. Nearly all of the pitchers who spoke to CBS Sports said their first time throwing at 61 1/2 feet came within a game. "We didn't get anybody to come in and explain to us why they did it; why we didn't get an All-Star Break; why we're not getting time off to practice," one pitcher said. "It was, you know, you lab rats deal with it. If you get hurt, too bad, we don't give a shit. That's everybody's concern, too: who's going to pay for surgeries when guys blow out? Who's going to be responsible when something happens?"

When asked if the leagues felt they had given the pitchers enough of a runway before making the change, White and MLB stressed that pitchers were aware of the plan coming into the season. An MLB spokesperson noted the leagues had originally agreed to move the mound to 62 feet, 6 inches in 2019, but that experiment was not conducted as planned. Further, White said he encouraged teams to "contemplate" what the 61 1/2-foot mound would mean for its pitchers "around Memorial Day." He claimed some teams heeded the league's advice by prepping as early as June, but that one club did not act until the final days.

"That one literally lands squarely on the shoulders of our managerial and coaching staffs because they were advised of this," White said of pitchers who felt unprepared for the mound change. "Some guys didn't think it was worthwhile. Some guys left it up to their players. Some guys said, 'hey, look, we're losing our best pitchers because of the number of transfers [to MLB organizations] this year; every time I communicate, I lose that guy."

White and the league's coaches have clashed in other respects, too.

Ahead of the switchover, West Virginia Power manager Mark Minicozzi and pitching coach Paul Menhart each made comments to Nick Scala of the Charleston Gazette-Mail suggesting they were being muzzled by the league about the mound move. "We are not allowed to have an opinion, the only opinions that matter are the league office," Minicozzi said, "and if we have an opinion we would be suspended indefinitely without pay."

Menhart added: "We've been forbidden to speak about it from [Atlantic League President] Rick White, under strict orders."

When asked about those comments, White dismissed the idea that the league has a gag order in place for its coaches or players. "We've never [forbidden] a manager from speaking about any on-field matter, this or any other test rule, or existing rule or equipment trial in our league," he said. "What we have advised all of our uniformed personnel, especially our managers and our coaches, is, when it comes to the relationship with Major League Baseball, our league needs to speak with one voice, not several discordant voices."

'It's not baseball anymore'

The voice of the Atlantic League has often attracted players by singing a siren's song of redemption. Down-on-their-luck veterans flocked to ALPB with the belief that it could serve as their return vessel to the affiliated realm. The league's "notable alumni" section is as long as it is varied. There are countless up-and-down types who populated big-league and Triple-A rosters before (and after) their ALPB stints; there are authors of remarkable comeback stories, like Rich Hill and Scott Kazmir; and there are even Hall-of-Famers and All-Stars, be it Rickey Henderson, Tim Raines, or Jose Canseco.

The tacit agreement between the league and its players went like this: in exchange for serving as a launching pad, where players could revive their careers, the league's teams would gain the legitimacy and publicity that comes from employing veteran ballplayers. Teams would also make more money the old-fashioned ways, by drawing more folks through the gates and by later taking a finder's fee of sorts when the players were reabsorbed into affiliated ball. The cycle would then continue over springs and summers for perpetuity.

Beyond rehabbing veterans' stock, independent leagues have filled an important role in baseball's ecosystem. They provide professional opportunities for players, coaches, and non-uniform personnel who may have been snubbed otherwise. Most of those individuals harbor major-league dreams, but few will realize them. They'll settle instead for modest careers in towns full of folks who might not be able to afford the big-league experience. The ones who do make it can encourage other dreamers to follow suit, again keeping the leagues flush with willing participants.

Spiritually, the Atlantic League remains a feeder league. The difference is in what they're trying to supply. It's no longer revitalized or forsaken ballplayers and office staff; now, it's data from stress-tested boardroom concepts. The league's quality of play has suffered as a result, violating their end of the understanding they had with players about pipelining their paths back to affiliated ball. The players have noticed.

"With all the rule changes, and the systems that are in place, the league's a joke," a pitcher said. "They've turned it into a complete mockery. It's not baseball anymore. I believe that MLB teams are seeing this, and they're going elsewhere to pick up players."

Lately, it feels MLB has been more interested in cutting players. Last winter, the league slashed more than 40 minor-league affiliates as part of its plan to increase individual minor-league pay without increasing total costs. An executive with an MLB team observed that the Atlantic League seemed well-positioned to benefit from the cuts. The players who lost their jobs during that process may not have been top-shelf prospects in the eyes of MLB evaluators, but they were of a higher quality than the lot usually available to independent leagues. (Not to mention the coaches, scouts, and office workers.) Add in those who took last year off because of the pandemic, and the conditions were met for a talent infusion on the independent circuit. Yet one player estimated that a handful of their team's roster had not played professionally prior to when they latched on this season.

The Atlantic League's quality of competition used to be regarded as Triple- or Quad-A-caliber. The players had to have legitimate professional experience to make it onto the field, they had to be capable of stepping into a Double- or Triple-A situation without missing a beat. The current version of the Atlantic League, in the estimation of one veteran hitter, falls closer to High-A ball. "It's almost felt like summer or college ball sometimes, because the quality is down this year," they said. "It's been frustrating."

The Atlantic League's website lists 70 players who have had their contracts purchased by another league since April, indicating there's still an appetite for quality ballplayers. MLB teams have abstained as of late, though, with zero ALPB contracts being transferred to them since July 20. The last time an MLB team brought up an ALPB hitter, meanwhile, was on June 20, when the Philadelphia Phillies purchased the contractual rights to catcher Logan Moore.

The drought isn't too surprising to one Atlantic League pitcher. They theorized that hitters, not pitchers, will be the ones MLB teams look down upon when it comes to the effects of the 61 1/2-foot mound. "I know that they're using all the analytical stuff they get off Trackman, like spin rate and all that with our fastballs and our breaking balls," they said about pitchers before shifting focus to the hitters. "I feel they're going to end up having an asterisk next to their name because they're the ones hitting at 61-6. Pitching-wise, it wouldn't bother anyone, but hitting-wise there's always going to be a question."

One hitter who spoke to CBS Sports acknowledged that he had moved up in the batter's box to combat the effects the 61 1/2-foot mound had on pitchers. Other hitters across the league have taken similar measures, according to pitchers.

Regardless of whether pitchers' or hitters' statistical achievements will be dismissed, or which sides' will be discredited more, it's evident that players are concerned about how the Atlantic League's experiments will impact their professional opportunities -- and not just as it pertains to MLB. Most of the league's players will never earn seven figures in a season, making seeming luxuries like a winter-league job all the more important for their finances. At absolute minimum, they fear other leagues will hesitate before looking their way, since no team wants a player who will require a reacclimation period when they're asked to play baseball under the standard rules and dimensions.

Those concerns were shared by most of the players who spoke to CBS Sports. Some are embracing the change and viewing it as a potential separator in the other direction: toward the betterment of their long-term prospects. "We don't know if this is a good or bad thing yet. They may use this next year somewhere, and then we can be like, 'Hey, I've already done this,'" Shuman, the Barnstormers reliever, said. "It's always good to try new things and get outside your comfort zone."

White, for his part, argues that the Atlantic League's partnership with MLB, experiments and all, offers players a golden opportunity to advance up the ladder. "There's no other partner league where you are going to have your results analyzed every night by a player development group [with] virtually every major-league team," he said. "You may be misinformed, or under misapprehension about just what major-league teams are looking for. You may not know the facts as it relates to the distance you're already throwing a baseball, because you're looking at it two dimensionally, not three dimensionally. And you may not be aware of the science that goes into this."

If players' careers are suffering in any way because of the rule changes, then the least ALPB and MLB could do to make amends would be to pay the players more or to provide better amenities. Life as an independent ballplayer is comparable to life in the minors, except worse in several regards. There's less security and upward mobility, and there are few advocates highlighting the sins committed against the players. Minor leaguers at least have organizations like More Than Baseball fighting on their behalf; independent-league players are largely on their own. Some independent leagues -- not the Atlantic League -- have even garnered reputations for missing payments to players.

Although ALPB's agreement with MLB is widely believed among the players to have included a financial component, there has been no trickle-down effect. As a pitcher put it: "Where that money went, I have no idea because it definitely didn't go to any of the food that we pay for, the places that we stay at ... [it] definitely didn't go to any of that."

Instead, players are having to make difficult decisions. A veteran hitter retired earlier this season when MLB interest failed to materialize. "I have a family, and an Atlantic League salary does not support a family," they wrote in an email. "I needed to do what was best for my family and move on."

A different player laughed when they were asked if their paycheck had improved now that the league is running experiments for MLB.

Yet another player noted that their team was reduced to eating pizza and fast-food sandwiches after games. That player wondered why the Atlantic League couldn't secure a catering deal or invest in better nutrition for the individuals who are risking their livelihoods to make the MLB partnership possible. "I'm still eating peanut butter and jellies after I work out," they said.

'We were threatened'

The Atlantic League is, in some respects, a convergence of baseball's past, present, and future. The independent-league system is a reminder of how teams found talent in the old days, before Branch Rickey created the modern farm system; the present, with strife between the players and management, is akin in broad strokes to what's going on at the big-league level; and the rule changes and experimentations that have helped create the strife are, to an unknowable degree and extent, likely to be weaved into MLB's future.

Several Atlantic League players who talked to CBS Sports expressed confidence that the MLB Players Association will reject any proposal that calls for a 61 1/2-foot mound as part of Collective Bargaining Agreement negotiations this winter. (The Atlantic League pitchers, for their part, seem to hold a greater resentment for the automated ball-strike system, which has since made the leap to the minors and seems imminent at the big-league level.)

While the Atlantic League's players have no union and are not represented by or connected to the MLBPA, their personal and professional concerns about their situation spurred them to pursue an organized act of labor ahead of the Aug. 3 switchover to the 61 1/2-foot mound, according to the accounts of several players. "Most of the guys were like, yeah, if we can do it, we would love to say, 'f--- these guys' and we're not going to pitch," one player said of the plans.

The same player explained that though most of the Atlantic League was on board with the walkout, they were unlikely to achieve full cooperation. The league's younger talents, who the player sympathized with, were disinclined to risk derailing or even outright ending their careers before they truly started.

The younger players never had to make a call, since soon enough the rest of the league became dissuaded from taking action after hearing about potential backlash. One player said: "We were told if we did this that there were certain [consequences] that could come with it." Another said: "We were threatened. 'You're going to be barred for life, and the Atlantic League is going to transfer over to the other independent leagues.'"

The genesis of the threats are unknown, even to the players. Several said they weren't sure where the talk about repercussions stemmed from. One player claimed that he first heard about the potential ramifications from an umpire during a game. A different player said they believed they heard it from a member of the coaching staff. Whatever the origins, the punishment aligns with a mechanism the Atlantic League has at its disposal: the suspended list.

Were a player to violate their contract with an Atlantic League team, say, by refusing to play in games because of a rule change, then the league could place them on the suspended list. That maneuver would not only prevent the player from signing with another Atlantic League team, it would complicate their chances of finding employment elsewhere in the baseball world. Other leagues are known to inquire on players' eligibility, just as they are known to be hesitant to sign a player who might agitate MLB or a partner league.

The Atlantic League did enact a brief grace period leading up to the implementation of the 61 1/2-foot mound. During the grace period, players could request trades or transfers from their teams to other leagues. The Atlantic League teams were under no obligation to fulfill those requests, however, and any transaction had to be deemed "fair" by the league, a provision that stifled activity and prevented a mass exodus. After the grace period ended, players were expected to play out the remainder of their contracts.

"We had some players request trades. We had some players express that they might use this as an opportunity to retire. We had some players say, 'Well, what if I just don't do it?'" White said when asked if players were able to opt out without repercussions after the enactment of the new mound. "In the first two cases, we accommodated those players. In the [third] case, we said, 'well, we aren't going to shackle you with a ball on a chain, but if you leave the club, there's consequences.'

"We tried to accommodate those players who said they would prefer to play somewhere else. The problem is, sometimes they aren't quite as coveted, or seasonality doesn't make that as easy as it might seem on the surface." (By "seasonality" White means how the Atlantic League started its season later than other leagues because of COVID-19; in other words, there was an imbalance in the impact a player could make in the Atlantic League compared to other leagues based on the number of games remaining on the schedule.)

An MLB spokesperson responded to the same question, about whether or not ALPB players could opt out without any strings attached following the mound change, with the following statement: "Any Atlantic League player who opts out is free to sign with an MLB Club if he wishes."

The players did express their dissatisfaction with the Atlantic League and the 61 1/2-foot mound by largely foregoing a Zoom call the leagues hosted ahead of the Aug. 3 change. Theo Epstein -- the former World Series-winning executive who's now a consultant with MLB -- was among the featured guests, yet White estimated that fewer than 20 of the league's players attended.

'[Manfred] cares about himself and one agenda'

The author John Steinbeck once wondered why progress resembles destruction. The Atlantic League's players must feel the same way when they reflect on where the league has diverged from the norm since agreeing to partner with MLB. What was once a haven for players hoping to find their way back into affiliated ball has now become another league's laboratory. One veteran player, who vowed he would not return for another season in the Atlantic League, said he couldn't understand why MLB chose this league to tinker with rather than one staffed by younger, less talented players. "It's terrible what the league has become, it's really a shame," a different player said. "I understand business is business and you think you made a business move to help the league, but the league didn't need help."

The players are adamant that the old Atlantic League was the idyllic setting, but it doesn't appear that its leadership agrees. Much as a stretched mind will never return to its original form, nor will the Atlantic League's rulebook return to its original dimensions.

White, who talks excitedly about survival in the minors being based on wits rather than the good television contracts of their big-league counterparts, says the partnership with MLB has been a "process of elucidation." The experiments ALPB have conducted for MLB have opened their eyes to previously unthinkable possibilities, including, he says, a new rule about defensive shifts (infielders must be on the infield dirt or grass, meaning no overshift alignments that spill into the outfield) and foul-pole colors (Lancaster's are now pink). White doesn't intend to stop tinkering, either. "You're gonna see us do some things that most people would never think a minor league would do," he said. "Some might seem wacky, but we have a purpose in trying to do everything we're doing. You'll see us come up with a couple of surprises next year that most people won't see coming."

Provided White stays true to his intended course, the schism between the Atlantic League's leadership and its players is unlikely to be healed or corrected. One side sees the experiments as its way of staying relevant, and as its way of partaking in the creation of baseball's future. The other, the ones entrusted with handling the vials, sees these measures as a facade for a cash grab at the expense of their careers and livelihoods, as well as the league's wellbeing.

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred's name came up here and there throughout conversations with players. It's clear that they view him as being as responsible for what's happening to the Atlantic League as any other individual. "He doesn't care about the players. He cares about himself and one agenda," a player said of Manfred. "The same thing with Rick White: make money, put fans in the seats. That's all they care about, ruining the game of baseball, but getting as much money as they can."

Who gets to define progress? Is it always a good thing? What happens to those who are left behind? The Atlantic League, the top independent baseball league in the country, is primed to serve as a case study for those questions.

"I care a great deal about the relationship with MLB, and because of that, I defer to them completely around all of our experiments," White said. "[At] the end of the day, they're the ones commissioning the experiments. Our job is to execute these tests as capably and as professionally as we can."

![[object Object] Logo](https://sportshub.cbsistatic.com/i/2020/04/22/e9ceb731-8b3f-4c60-98fe-090ab66a2997/screen-shot-2020-04-22-at-11-04-56-am.png)