In the seventh inning of the Dodgers' eventual win over the Cubs in Game of the NLCS (LOS 5, CHC 2), L.A.'s fill-in shortstop Charlie Culberson attempted to score from second on a Justin Turner ground-ball single to left. Kyle Schwarber with the throw, and Willson Contreras with the tag ...

Had the call on the field stood, the Dodgers would've had runners on first and second with two outs and a 4-2 lead. Per basic win expectancy, that still gives them a 92.6 percent chance of winning the game. Given that Kenley Jansen was rested and looming (he'd log a four-out save), this call almost certainly didn't flip a Cubs win into a Cubs loss. So be mindful of that before rioting.

OK, so the controversial plate-blocking rule has made its presence acutely felt in this one. The rule, informally known as the "Buster Posey rule" for his violent 2011 collision with Scott Cousins, has been in force since the start of the 2014 season and tweaked since. Anecdotally, fans and players don't seem to like it all that much. Regardless, it's a rule, and rules tend to be enforced on the field.

Speaking of which, here are the relevant portions of Rule 6.01:

"Unless the catcher is in possession of the ball, the catcher cannot block the pathway of the runner as he is attempting to score. If, in the judgment of the umpire, the catcher without possession of the ball blocks the pathway of the runner, the umpire shall call or signal the runner safe.

...

"A catcher shall not be deemed to have violated Rule 6.01(i)(2) (Rule 7.13(2)) unless he has both blocked the plate without possession the ball (or when not in a legitimate attempt to field the throw), and also hindered or impeded the progress of the runner attempting to score. A catcher shall not be deemed to have hindered or impeded the progress of the runner if, in the judgment of the umpire, the runner would have been called out notwithstanding the catcher having blocked the plate."

So in essence a catcher can't block the plate unless you have the ball or are in the direct act of receiving the throw. As for the latter condition, here's some additional clarification from the MLB rulebook ...

Notwithstanding the above, it shall not be considered a violation of this Rule 6.01(i)(2) (Rule 7.13(2)) if the catcher blocks the pathway of the runner in a legitimate attempt to field the throw (e.g., in reaction to the direction, trajectory or the hop of the incoming throw, or in reaction to a throw that originates from a pitcher or drawn-in infielder). In addition, a catcher without possession of the ball shall not be adjudged to violate this Rule 6.01(i)(2) (Rule 7.13(2)) if the runner could have avoided the collision with the catcher (or other player covering home plate) by sliding.

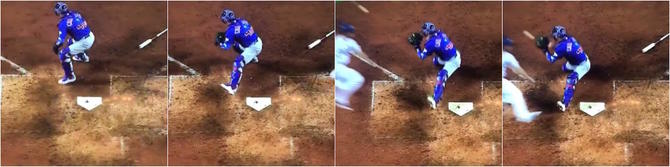

So this is relevant to the landmark Contreras v. Culberson case. This portion of the rule specifies that the act of fielding the throw must force the catcher into the runner's path. That qualifier is probably what motivated the overturn. Let's have another look in still format ...

In the first frame, you see Contreras set up without blocking the plate (or at least the entirety of the plate). Then in the second frame he begins setting up to receive the throw. In the third frame, the throw from Schwarber appears, and it looks angling a bit toward the inside of the plate. In the fourth frame, the throw is almost in Contreras' mitt, and we see him complete his step in front of the plate.

The question is did Schwarber's throw take Contreras in front of the plate? Not to that extent, probably. Some move into the runner's path was probably in order. Contreras likely extended his leg farther than he needed to, and that was surely an intentional effort to complicate Culberson's slide. Is there enough "plausible deniability" on Contreras' part? Does the inward angle of the throw give him enough cover to make that plate block?

This is where we're going to separate into two camps. This is also where I'll indulge in a spirit of the rule argument. I don't mind legislating to protect catchers, but I do mind absolutism when we're talking about a rule that's unpopular with consumers of the sport, managers, and a large percentage of players. (Before you come at me with any overwrought comparisons, please bear in mind that we're talking about the rules of a game and not criminal law.) When wielding a rule like that, you should be damn sure that a violation has occurred. A letter-of-the-law approach may lead you to conclude that Contreras illegally blocked the plate, but there's an argument that he didn't. It was also, if this has any relevance, a beautiful play on the part of Contreras. His straddling the line of allowable/illegal is part of the brilliance of the play, it says here.

The rule itself is fine if it's wielded carefully and judiciously. On Saturday night in L.A., it wasn't.

![[object Object] Logo](https://sportshub.cbsistatic.com/i/2020/04/22/e9ceb731-8b3f-4c60-98fe-090ab66a2997/screen-shot-2020-04-22-at-11-04-56-am.png)