J.T. Daniels has a simple solution to what is becoming one of the most contentious reforms in NCAA history.

"You shouldn't have to enforce loyalty with a rule," said the 18-year-old blue-chip quarterback who signed with USC in February. "A coach can leave whenever he wants. There's no reason a player shouldn't be able to [transfer and be eligible] right away."

Daniels has yet to enroll in college, but he has already boiled down the essence of perhaps the most thorough review of the NCAA's transfer rules.

An NCAA transfer working group -- the fourth or fifth such iteration to address the subject -- has been given a mandate to develop proposals by the NCAA Board of Governors. Those proposals could come as soon as next month for passage in June.

Since NCAA rules were codified in 1951, a national rule has required players transferring schools to complete "a year in residence" to get their academics in order.

Since at least 1964, coaches and/or schools have been able to "block" those transfers from certain schools for what amount to be competitive reasons. Before that process even started, for decades, players have been required to obtain "permission to contact" a new school from their transferring school.

Those rules seem increasingly antiquated, unfair and possibly illegal. Regular students can transfer at will without restriction. As mentioned by Daniels -- the record-setting quarterback at Santa Ana (Calif.) Mater Dei High School -- coaches can depart at any time leaving dozens of athletes who committed to their style, personality and program in a lurch.

We could be living in a radically different world if the rules are implemented in time for the 2018 football season (and 2018-19 basketball season).

It seems almost a certainty that players will no longer have to seek "permission" to transfer. Rather, they will merely "notify" their coaches they are leaving.

Also, there doesn't seem to be significant change to the graduate transfer rule. The 13-year-old rule allows players who have graduated to finish their remaining eligibility at another school.

Even then, schools still have the power to block a player from competing right away. It seems absurd: A player with his degree has to sit out a year, attending graduate school (and getting financial aid) on a competitive whim from his previous school.

On the opposite end, coaches are concerned about full-on "free agency" should there be a major rule change with players able to transfer at will without restriction.

"All the sudden they're leaving in masses," suggested Daniels' future coach, USC's Clay Helton.

The working group says it is not interested in that concept. What is becoming clear is one size does not fit all. There are so many diverse interests that real reform will be a challenge.

But if there is one thing that gets the NCAA's attention, it's legal liability. The transfer rule has long been criticized for possible anti-trust violations.

A detailed proposal by the Big 12 earlier this year seems more than fair. Most significantly, it suggested players could transfer and be eligible immediately if a coach leaves or gets fired.

"Basically, we're saying kids can go anywhere they want," Iowa State athletic director Jamie Pollard said. "For the first time ever in college athletics, the student-athlete is empowered."

The working group says it is "interested" in studying the Big 12 proposals.

Some coaches reacted with a sense of panic. Nebraska's Scott Frost said he supported free movement if a coach leaves but added: "I think there's been some proposals to make transfers free and never have to sit out. My opinion of that would be a disaster. … I think that'd get messy and ugly."

On the other hand, there is a feeling that athletes have been unfairly indentured for decades -- tied to a school by an antiquated rule that was passed in a different time for a different reason.

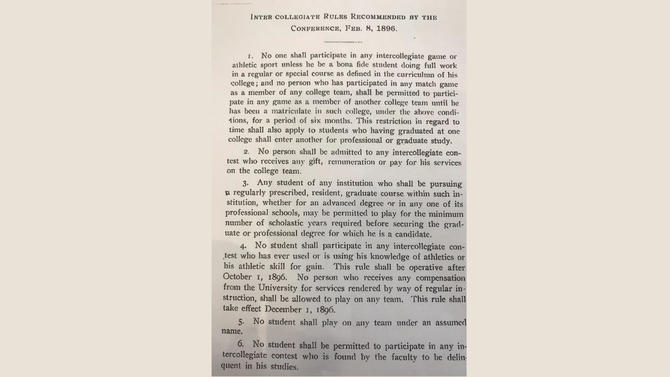

The origins of the transfer rule can be traced back to 1896, implemented by a precursor of what would later become the Big Ten. Back then, athletes sometimes weren't even enrolled -- playing the emerging sport of football for the highest bidder.

In that sense, college athletics has had 122 years to get it right. That it has not already reflects how complicated reform has become.

"Four working groups have taken a crack at this [transfer issue], and they're all populated by smart people," Big 12 commissioner Bob Bowlsby said. "If it was easy, we would have figured this out a long time ago."

A one-size-fits-all solution seems almost impossible. When the working group revealed it was considering an academic benchmark -- the equivalent of a B to transfer immediately -- there was reaction on both sides.

"I like that because it keeps you solid in school," NC State guard Braxton Beverly said. "You go to college for school but you use basketball to hopefully make a living that way, that would be a good incentive."

However, some pointed out that a "B" at Stanford isn't the same as a "B" at, say, Toledo. And would academic advisors manipulate players' grades so they don't reach that threshold to keep them on the roster?

"You've got the issue that, 'Gee, it's harder at some schools than it is at others,'" Bowlsby said. "And you don't have to be very hard into it to realize [an academic benchmark] cuts very hard across racial lines."

Athletes in men's basketball, football, track and baseball typically have lower graduation rates than other sports. The NCAA certainly doesn't want to go down that road. Its controversial Proposition 48 that passed in 1986 caused significant division.

Former Georgetown coach John Thompson once sat out two of his own games in protest over the entrance-requirement rule that was perceived as discriminatory.

NCAA legal representatives have told the transfer working group an academic benchmark is legally "defensible," according to a source.

"We all know that the Board, they want something to change," said a source close to the working group. "They've kind of put this group in an impossible situation that is impossible to fix."

Notre Dame athletic director Jack Swarbrick called the transfer issue "very complicated." He added, "[I'm] not sure there is a consensus among the membership or constituent groups. … Not a result of self-interest so much as the intrinsic differences between schools and sports."

The current football transfer rate of 9 percent is well below the overall athlete rate of 6.5 percent. Baseball actually leads the way with a 19 percent transfer rate, followed by men's basketball at 15 percent.

Further complicating matters, only five sports require transfer students to sit out – football, men's and women's basketball, baseball and hockey. The Big 12 proposed that, at least in a sense of fairness, athletes in all sports have to sit out.

"You're treating the student-athlete different than everybody else on that campus," Gonzaga AD Mike Roth said. "Nothing stops the chemistry major from leaving Gonzaga and going to the University of Washington.

"The crazy part is, it's only certain sports."

Certainly, too much power has been given to coaches/schools in transfer matters. The rule was instituted for academic reasons. But schools have sometimes awkwardly and arrogantly used it to deny players for competitive reasons.

In 2017, Kansas State coach Bill Snyder blocked former receiver Corey Sutton from transferring to a list of 35 schools --- more than a quarter of FBS -- out of nothing more than pure spite. Sutton lost an appeal, but the appeals committee was overruled by then-AD Gene Taylor.

Miami backup quarterback Evan Shirreffs was denied a graduate transfer within the ACC and nonconference opponents on the Canes' schedule in 2018 and 2019. He won a partial victory on appeal and last week tweeted he was headed to Charlotte.

Notre Dame's Everett Golson and Louisville's Shaq Wiggins were similarly blocked as graduate transfers by the high-powered coaches at those schools. Brian Kelly and Bobby Petrino, respectively, eventually relented.

That sort of heavy-handed control is as least partially responsible for the Board's call for reform.

"Coaches don't like letting players go," BYU AD Tom Holmoe said. "Coaches are prideful. ADs, too. Realistically, when you listen to the full argument outside of athletics, it doesn't make any sense."

If a player wants to transfer, Holmoe tells his coaches, "You have to let them go. You can't hold onto them. On the other side of it, there are some kids that aren't going to be happy no matter what. If we didn't do a good enough job, let them go somewhere else. Let them find their way."

At the other end of that discussion is a team like Nevada, all five starters for the men's basketball team that advanced to the Sweet 16 are transfers.

Coaches are struggling enough with the 13-year-old graduate transfer rule. Latest figures show that 40 percent of all Division I players who come directly from high school leave their original school by the end of their sophomore year. Coaches are concerned about roster management. Players are concerned about maximizing a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

"Ultimately, it's not that coaches' decision if a player leaves, and it's not a player's decision if a coach leaves," Daniels said. "It's purely up to that person themselves. If it's the best move for them, there should be nothing restricting it."

Status quo advocates argue that players who stay at one school throughout their careers are more likely to graduate. That parallels a phrase in the National Letter of Intent that reminds prospects they are signing with a school, not a coach.

In this modern age, though, that is almost laughable.

"Of course you [commit to the coach]," Beverly told CBS Sports.

Beverly was the subject of a contentious transfer last year. He had signed with Ohio State when Thad Matta was fired last June. Beverly, who had enrolled as a freshman, petitioned for an immediate transfer but was denied.

The NCAA later relented citing "more information" gathered on the subject.

"When you go to the school, it's the coaches that come out to recruit you bring you to that school," Beverly added. "You want to pick the school for the school, but [the coach is] where you go to for your help if you're struggling. You want to talk to your coach. That's who you're most comfortable with."

While that commit-to-a-school phrase is included in the NLI, nowhere in that document does it say a school can block a prospect from transferring to certain schools. That's why Bowlsby paraphrased the Board of Governors mandate that suggests new transfer language "should be the least restrictive it can be."

What is becoming increasingly clear is the line-in-the-sand mandate may be delayed just like it always has been. Big East commissioner Val Ackerman suggested to CBS Sports this week that the historic legislation could get "stalled."

That might be the first time such a high-ranking college official has suggested a delay in this process. Through its reporting, CBS Sports has learned that other administrators doubt whether both transfer and basketball reform can be accomplished in the same year.

The NCAA is currently waiting for recommendations from the so-called Commission on College Basketball after the FBI investigation scandal in basketball.

"The FBI thing has really been a black eye on us," Roth said. "My fear is that if a kid today says, 'I don't like my coach because he yelled at me in practice,' and we make it to easy to transfer, are we going to open a new can of worms to new outside influences?"

Ackerman says it all may be too much change to digest at once for NCAA membership.

"I do think it's possible that the work of the transfer working group … may get stalled," she said, "especially in terms of basketball [reform] while all this is unfolding."

Those first transfer rules came from the Western Conference -- that precursor to the Big Ten. The Big Ten was able to produce for CBS Sports a rulebook from that old Western Conference in 1896 that mandated transferring athletes had to sit out "for a period of six months."

Consider that, four years after the sport of basketball was invented, administrators were worried about tying players to schools for competitive reasons. That was in the age of the so-called "tramp athlete" in football detailed meticulously by Big Ten Network anchor Dave Revsine in his 2014 book "The Opening Kickoff." Players could basically be mercenaries -- not even enrolled -- playing for whatever school offered them the best opportunity.

Michigan coaching legend Fielding Yost once left West Virginia in his final year as a player to suit up for Lafayette in an upset win over Penn. He then returned to the Mountaineers.

Seven of the 11 players on the 1893 Michigan team were not enrolled.

Those early Western Conference schools agreed to the rule, then immediately ignored it, basically for competitive reasons. They couldn't help themselves.

The regents at Wisconsin overruled the faculty in allowing star kicker Pat O'Dea to play even though his status as an actual student was in question.

The game eventually cleaned itself up, sort of. The first set of NCAA bylaws in 1951 -- many adopted from those ancient Big Ten texts -- still exist as the foundation today's transfer rules.

Whether they remain fair or not, we're about to find out.

"There are a lot of rules that don't make much sense," Daniels said. "When you look at that rule, I don't think it makes any sense [that] a kid should have to sit a full year of his college life to transfer."

![[object Object] Logo](https://sportshub.cbsistatic.com/i/2020/04/22/e9ceb731-8b3f-4c60-98fe-090ab66a2997/screen-shot-2020-04-22-at-11-04-56-am.png)