PITTSBURGH -- Start at PNC Park, the exact point on the compass that this year's Pirates will take the October baton from their 1992 predecessors and joyfully begin the task of melting ice hardened over 20 years of searing hardball pain and jumbled emotions.

Drive due north, a mere 30 miles or so, and you're rolling up the driveway to Sid Bream's two-story, brick house atop a hill nestled in the woods. He is surrounded by white-tailed deer, his framed 1992 Braves World Series jersey and still, nearly every single day that he leaves the house, he is identified by someone for his triumphant Game 7 slide across the plate in the '92 NL Championship Series.

The slide that sucked the wind out of this city and sent its baseball rolling downhill, for good, for the next two decades.

Now point the rental car east, cutting across the lush, rolling hills of central Pennsylvania. Some 140 miles later you're parking outside the Main St. Café and Sports Bar in the tiny borough of Alexandria, Pa., population 346. Stan Belinda, the Man Who Threw the Last Playoff Pitch for the Pirates, lives on a farm a few miles off of what passes for the main highway in this remote area.

The pitch that spawned an avalanche of hate mail and birthed a tortured baseball soul that is still, apparently, scarred by deep wounds that never completely healed.

Trace that line from PNC Park ... up to Bream's house ... over to Belinda's farm ... and back again ... and what results is the closest thing there is to a baseball Bermuda Triangle, a time and space continuum into which the Pirates disappeared with the crack of Francisco Cabrera's bat on that long ago Oct. 14 in Atlanta.

That both the affable Bream and the reclusive Belinda, both Pennsylvania natives forever linked by one play -- the ecstasy and the agony -- live a fairly short drive from each other today is almost unfathomable.

That the song Cold October by the band Escondido randomly plays on the radio as the car closes in on Bream's driveway one recent morning with a hint of autumn in the air seems just one more eerie echo reverberating across the years. …

Sid Bream's couch

Just last night, Bream and his wife of 30 years, Michele, went to dinner with friends. And the same scene that has been playing out as if on a video-replay loop for two decades unspooled again: The maitre d' instantly recognized him.

"If I go out in public at all, somebody is going to come up and tell me they don't like me, or, 'I remember exactly where I was when you slid.'" Bream says, sitting on his basement sofa in Zelienople, Pa., a framed newspaper picture of his slide past Pirates catcher Mike "Spanky" LaValliere and into history on the wall behind him -- along with a couple of framed Braves jerseys and autographed bats.

|

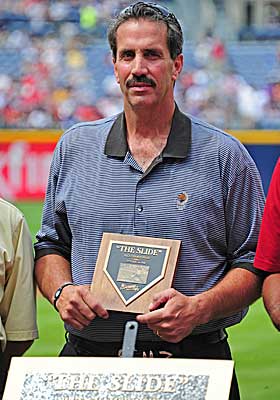

| The Braves honored Bream in 2012. (Getty Images) |

He's heard it all. People have told him of bets made in which they would have had to go streaking outside, around the house, if Pittsburgh had won that night. Pirates fans have described putting their fists through walls in fits of anger. Braves fans have detailed accidentally sticking hands through ceiling fans leaping up in jubilation.

"Most ballplayers go into obscurity," Bream says. "I can't sit here and name guys from a lot of World Series teams. That event, obviously, is something that's allowed me opportunities."

Now 53 and still trim, Bream is working on completing his college degree, in general studies, from Liberty University (thus, a long-ago promise to his college coach will be fulfilled). He does some corporate speaking and some Christian motivational speaking. He remains involved in both Braves and Pirates alumni events. He spent one season, 2008, as hitting coach for the State College Spikes, Pittsburgh's Class A affiliate.

He still recalls that spring day in Bradenton, Fla., when someone from the Pirates' organization introduced him as a new Spikes coach, remarking that since the Pirates' announcement, "half of the calls we've gotten have been negative, and half have been positive."

"Now, most of the negative stuff I get is fun negative," Bream says.

Not so during those early days close to, as he refers to it today, "the event."

"Somebody called a night or two after and said, 'I'm going to kill you and your whole family,' " Bream says.

He still has no idea how that particular deranged lunatic obtained his unlisted phone number. About a month ago, after the death-threat anecdote appeared in a Sports Illustrated story, one of his neighbors approached him.

"I can't believe someone could be that terrible," she said.

Lady, if you only knew. ...

Stan Belinda's vapor trail

This is not one of those stories where the years melt away and the pain dissipates and everyone smiles in the end. Sometimes, when real time freezes in real life, the thaw just never quite sets in.

The last man on the mound in a Pittsburgh playoff game has rarely been heard from since his 2000 retirement. Belinda created far more noise with one final Game 7 pitch in 1992 than he's ever made since.

"People were really hard on him when that happened," says Pirates broadcaster Bob Walk, who was warming in the Pittsburgh bullpen that night when the trap door opened beneath Belinda and swallowed Pittsburgh's World Series invitation whole. "Everybody wants to blame someone, point fingers, every time anything bad happens."

So the venom spewed and the hatred spread and death threats were issued Belinda's way, too.

"I can remember him almost in tears after the game," Walk says. "I can remember him saying, 'It wasn't my fault. It wasn't my fault.'

"I felt so bad for him. The weight of the whole Pittsburgh baseball world came crashing down on him."

Belinda would go on to pitch eight more seasons, some pretty good, some not so good. The Pirates sent him away at the July 31 trading deadline in 1993. The pain still was just too raw. Reminders were everywhere. Right or wrong, trust was fractured. Some in Pittsburgh still say that every time manager Jim Leyland looked his way after that ... well, maybe the trade would be best for everyone.

He was employed in bullpens in Kansas City, Colorado, Cincinnati. He surfaced as a solid set-up man in Boston to closer Rick Aguilera as the 1995 Red Sox sprinted down the stretch. The Indians swept them in the Division Series.

|

| Stan Belinda lives on a farm in Alexandria, a tiny borough in central Penn., pop 346. (CBSSports.com) |

A country boy practically from birth in State College, Pa., Belinda came from a farm and would return to a farm. Upon signing with the Red Sox about a week after the end of the 1994-95 players' strike, he explained that the deal came together just after he planted eight acres of alfalfa.

In 1998, Belinda was diagnosed with the early stages of Multiple Sclerosis. He pitched two more seasons. And wouldn't you know it: In 2000, he finished his career with, of all teams, the Atlanta Braves.

Though he lives roughly two hours from PNC Park, none of the current group of Pirates can ever recall seeing him there. Every now and again, he will show up in Altoona, Pa., home of the Pirates' Double-A affiliate and not far from his farm. This spring he worked the telecast of an exhibition game between the Pirates and Curve in Altoona.

But Belinda did not return phone messages from a couple of longtime acquaintances in the Pirates organization attempting to help arrange an interview for this story. And finally, through one of the Curve employees, Belinda politely sent word that he would prefer not to talk, period.

Sometime within the past few years, he changed his cell phone number, and some old friends cannot even get in touch with him.

"I haven't talked to Stan since spring training of '93, or just after the start of that season," says LaValliere, the man whom Belinda's final Game 7 pitch never reached. "I haven't had any contact with him at all.

"He was a quiet guy. Grew up in rural Pennsylvania. And that's his comfort zone."

Ninth Inning, Game 7, 1992 NLCS

Wheels had rarely spun as quickly as they were spinning in ear-splitting, Tomahawk Chopping, pressure-cooking Atlanta Fulton County Stadium when the Pirates dropped Belinda into, literally, a no-win situation.

Save situation? Yes, if you happened to be a magician.

The bases were loaded with nobody out when Leyland summoned Belinda. The Pirates were leading 2-0, only three outs from the World Series.

First batter, Ron Gant, poked a sacrifice fly to left to make the score 2-1.

Then Damon Berryhill walked on a 3-1 pitch, the Pirates to this day believing that Belinda had him struck out at least once, if not twice. But plate umpire Randy Marsh was known as a "hitter's umpire" who wasn't likely to give a borderline pitch to the pitcher.

That Marsh was even behind the plate is another layer to this novel of a story. The evening had started with John McSherry as the plate umpire. But McSherry, who would die of cardiac arrest on the field on opening day in Cincinnati only four years later, took ill early and had to leave. Stuff happens.

Just like, earlier in the inning, before Belinda's arrival, the normally sure-gloved second baseman Jose "Chico" Lind had booted a David Justice ground ball. Which contributed to the bases-loaded jam.

Now, after the Berryhill walk, the bases were full again. Brian Hunter popped to short.

Two out, and little-used Cabrera was batting for pitcher Jeff Reardon. And here is where another layer of lore appears: In left field, Pittsburgh's Barry Bonds was playing particularly deep, back toward the warning track. From his position in center, Andy Van Slyke, some people swear, hollered and motioned for Bonds to scoot up, to play more shallow. Bonds blew him off.

The count went to 2 and 1. Belinda threw a fastball outside. Somehow, Cabrera whipped his bat through the zone quickly enough to pull a sharp single into left field.

From third base, Justice came sprinting home. 2-2.

From second base, where he had established a shockingly large lead, Bream came galloping around third. ...

Down the line with Bream

Bream always came home to Pennsylvania because he never wanted to leave in the first place. He went to high school in his native Carlisle, home of Jim Thorpe. When the Pirates acquired him from the Dodgers in Sept., 1985, as a player to be named in the Bill Madlock deal, he thought things could never get better.

When they cut him loose as a free agent following the 1990 season, he literally shed tears. He still speaks reverentially of a couple of old Pirates coaches, Bill Virdon (who also managed the Bucs in 1972 and 1973) and Milt May.

Now Cabera's ball was bouncing in front of Bonds and third-base coach Jimy Williams was waving him home and. ...

"I look at Steve Bartman," Bream says, name-checking another infamous October character, the Cubs' fan who was vilified in 2003 for interfering with that foul ball into the stands that some initially thought Moises Alou could have caught, a pivotal moment in Game 6 of the NLCS. "I look at that young man, who ... everybody in the whole world would have done the same thing.

"Because of that play, he's been ostracized, received death threats. I was just doing my job. Someone in the same shoes as me, they would have given everything, too."

As he steamed home, Bream was giving everything on a right knee that had undergone five surgeries.

"I wasn't Deion Sanders, but I used to go from first to third with the best of them," he says of his pre-surgery days. "I think I still own the record for stolen bases by a first baseman for the Pirates."

Before his sprint home started, he was fully expecting to be replaced by a pinch-runner. When that didn't happen, with two out, Bream crept nearly one-third of the way toward third base with his lead.

Even at that, an on-the-line throw from Bonds probably would have nailed him. And had Bonds scooted in a few steps. ...

Bream still sees this play develop every time he goes out on a speaking engagement.

"Stan Belinda, I know where his concentration was, and he allowed me a huge lead," Bream says. "With my leg situation, I would not have been able to push with my right knee to get back to second base.

"If they had had a play on, I was dead. I would have been the goat."

It was Terry Mundorf, his old coach at Carlisle High, who taught Bream how to slide. Then Al Worthington, at Liberty University. Then any number of minor-league coaches.

"It wasn't that great of a slide," Bream says. "You're supposed to slide on your butt, not your hip. But with my knees, I was going to slide no matter what. I wasn't going to plant and go in a different direction because my knee wasn't going to take that."

It was at that point when bedlam and heartbreak met.

Down the highway with Belinda

To get to Belinda's Pennsylvania, you drive west on U.S. Route 22 past the Tractor Supply Company, the Drive-Thru Beer Barn and, fittingly, Ghost Town Trail. You cross the Cresson Ridge Summit of the Allegheny Mountains -- 2,400 feet elevation -- and then drive some more, out beyond Beer Bellies Food and Liquor and the Christmas Tree farm.

Alexandria is a tiny little out-of-the-way place with a volunteer fire department, a First Presbyterian Church and a "downtown" that consists of about three blocks and one four-way stop sign. Aside from its natural beauty, the area is known for world-class trout fishing and sand that, for whatever reason, is tremendous for glass making.

Inside the Main St. Grill and Sports Bar is about what you would expect: Autographed pictures and assorted memorabilia that are veritable shrines to the local teams. The Pirates. Steelers. Penguins. Penn State. Pitt. Others are represented as well.

It is a step back in time, with photos on the wall not only of Willie Stargell and Roberto Clemente, but of long-forgotten Pirates like Dave Giusti, Bob Moose and Gene Alley.

There is not one photo, or autograph, or anything, featuring Belinda.

Bill the bartender explains how Belinda bought the farm down the gravel road and up on a ridge, several miles off the main highway, and won't let anybody up there anymore. Someone else says he heard Belinda charges people to hunt up there, wistfully explaining that, before Belinda purchased the property, it is the only place he ever saw three six-point bucks.

Mostly, people say, he keeps to himself. He does not appear to be well-liked in this area or, more specifically, in this tavern.

"People see him at Wal-Mart and, it's never personally happened to me but I've heard a couple of people say this, people will say, 'Hi,' and he'll say, 'Hi,' back to them, but he'll cordially refuse to sign an autograph," says Mike McCormick, 48, who lives in nearby McConnellsburg.

Two others say that Belinda strung a cable across the gravel road leading up toward his property to keep people away, but township officials made him remove the cable because the road also serves as an access way to the local watershed and reservoir.

"You'd think in a small town he'd be less of a prick," McCormick says. "I don't want to speculate on his situation, but certainly he's got a lot of money. He doesn't have to worry about that. If I was in his situation, I'd be pumping hands all day long.

"Whatever. To each his own."

Some who know Belinda from the baseball world think those stubborn Game 7 scars have deepened over the decades. Others nod their heads in acknowledgement: Yes, that sounds exactly like Stan. Anti-social, dirt farmer at heart, even ranting and raving during his playing days about efforts to keep people off of his property back home.

"He was always a backwoods guy," says Steve Blass, the 1971 Pirates World Series hero and highly popular team broadcaster who was in the booth for Game 7 in Atlanta. "Maybe there's a decent chance that if he had gotten the save or win that night, it might have been the same reaction: He'd rather be up there with a gun in his hand doing some hunting.

"It doesn't make him a bad guy, bottom line."

On my way out of town, I drove up that gravel road and past the farm, hoping maybe I would spot Belinda outside, maybe make one more effort to talk. But nobody was around, and I certainly did not want to pull in and knock on his door unannounced.

Some doors, maybe they're just not meant to open.

Cold October

They say the next morning in Pittsburgh moved in slow motion. Seemed like half the city called into work sick. And the Pirates had won the World Series only 13 years earlier, beating the Orioles in 1979.

Nobody knew then that Belinda had just thrown the last October pitch for Pittsburgh until -- who? Francisco Liriano, 21 years later?

"In that one game, so many things happened," Walk says. "He never should have been in that position.

"It's almost like the Kennedy assassination, the Zapruder film. There are so many theories on what happened, and what could have happened. Was Berryhill out? Should Bonds have moved in?

"I've never seen anything in my life dissected like that. And people look at it like it decided the World Series. It was just to go to the World Series and, if I remember right, get beat by the [Blue Jays]."

Though they now live within three hours of each other, Bream cannot recall seeing Belinda over the years since. From time to time, Bream makes appearances through both the Braves and Pirates Alumni Associations, and there have been a couple of events in Pittsburgh over the years where he noticed Belinda's name on the list of those expected to appear. But, Bream says, he's never seen him.

"He was a great guy," Bream says. "He was a country boy who had a great career. Unfortunately, when that keeps being brought up, I can only imagine some of the questions.

"I wouldn't want to talk myself. That's not what I'd want to be known for."

Today, Bream is a regular at Braves fantasy camps and, from time to time, plays in Pirates alumni golf outings. An avid Hoyt bowhunter, he's been to Africa twice, and he’s hunted elk, buffalo, turkey, caribou, Dall sheep and alligator all over North America. Next spring, he's hoping to go after a mountain lion.

"At some point," he says. "I'll probably start looking to get back into baseball."

It has been, after all, five years since his season coaching in the Bucs' minor-league system. And Bream knows that the longer he stays away, the more difficult it will be to get back into the game. Even for a man whose Game 7 knee brace from '92 has been on display in the Braves Museum at Turner Field for years.

The locals say Belinda helped coach his son's baseball team at Juniata Valley High ("Go Hornets!"), and the Pirates who saw him in Altoona this spring said he looked and sounded good. Happily, by all accounts, Belinda seems to be keeping the MS under control.

Other than the infrequent sightings, though, he remains mostly a ghost from Baseball Past in Pittsburgh.

"You look back, it clearly was not Stan's fault," says Pirates hitting coach Jay Bell, the shortstop on the '92 team. "He was on the mound, the focus of everybody's vision there on the bump, and that's where people look.

"But who knows? I could have been positioned a little differently. Barry could have come up and made a better throw. ..."

LaValliere adds: "It probably is as unfair a thing as there could possibly be, to blame Stan. I find that just ludicrous. There's not one guy. We've all heard the, 'Spanky if you were just 6-feet tall, he was out.' They blame Chico. They blame Barry. They blame Belinda.

"When you look at it, could we have done better in the series? I don't know. Could we have scored one more run earlier in game?

"Unfortunately, this is a team loss. It's a finger-pointing thing. He did it. He did it. No, he did it. I don't think any of us to this day pointed a finger at each other.

"It was a tragedy. It was the lowlight of all of our careers."

Maybe this year's Pirates can help lighten the baggage all of those guys from '92 have lugged around all of these years. LaValliere, bitter for years after the Pirates unceremoniously released him in the spring of 1993, accepted manager Clint Hurdle's invitation to work as an instructor at camp this spring.

And for the first time, LaValliere bought the MLB Extra Innings package at home in Bradenton, Fla., and followed along with the Buccos all summer.

Bream watched all season, too. And when he was out of the house, he tracked the scores on his cell phone app.

"I've been pulling for them ever since then," says the man who started the baseball rolling downhill in Pittsburgh 20 years ago. "To me, it has been hard to watch.

"I'm tickled to death with where they're at. I'm hoping and praying they can put it all together."

So is an entire new generation of fans who know the names ... but who are far too young to have ever watched Bream and Belinda play.

Bream has four children now and one of them, Michael, is a youth pastor in Keller, Texas. Barely 6 when his dad slid across the plate that October evening, Michael now is 27 and knew exactly where he wanted -- needed? -- to be on Monday, Sept. 9, when the Pirates clinched their first winning season since 1992 in the Ballpark in Arlington.

"Hey, dad," Michael said excitedly over the telephone when he called home that evening. "Can you believe a Bream was there when the Pirates won No. 82?!"